High school sports are a cherished part of american society, but they can have serious mental health repercussions if the proper precautions are not taken.

Earlier this season, after repeated helmet-to-helmet contact at football practice, junior Jake Todd knew something wasn’t right.

“It hurt so bad,” he said. “It felt like there was a knife sticking into my brain.”

Todd had suffered a concussion.

“For the next couple of days, I couldn’t focus on anything, and my head was killing me. Even the lights in classrooms were giving me headaches,” Todd said.

Todd’s circumstance is not an unusual one. The severity of concussions in high school sports has often passed under the radar of officials, parents and coaches. But in light of recent studies being conducted on concussions, and the increasing number of concussions suffered annually, the issue has finally received the attention it is due.

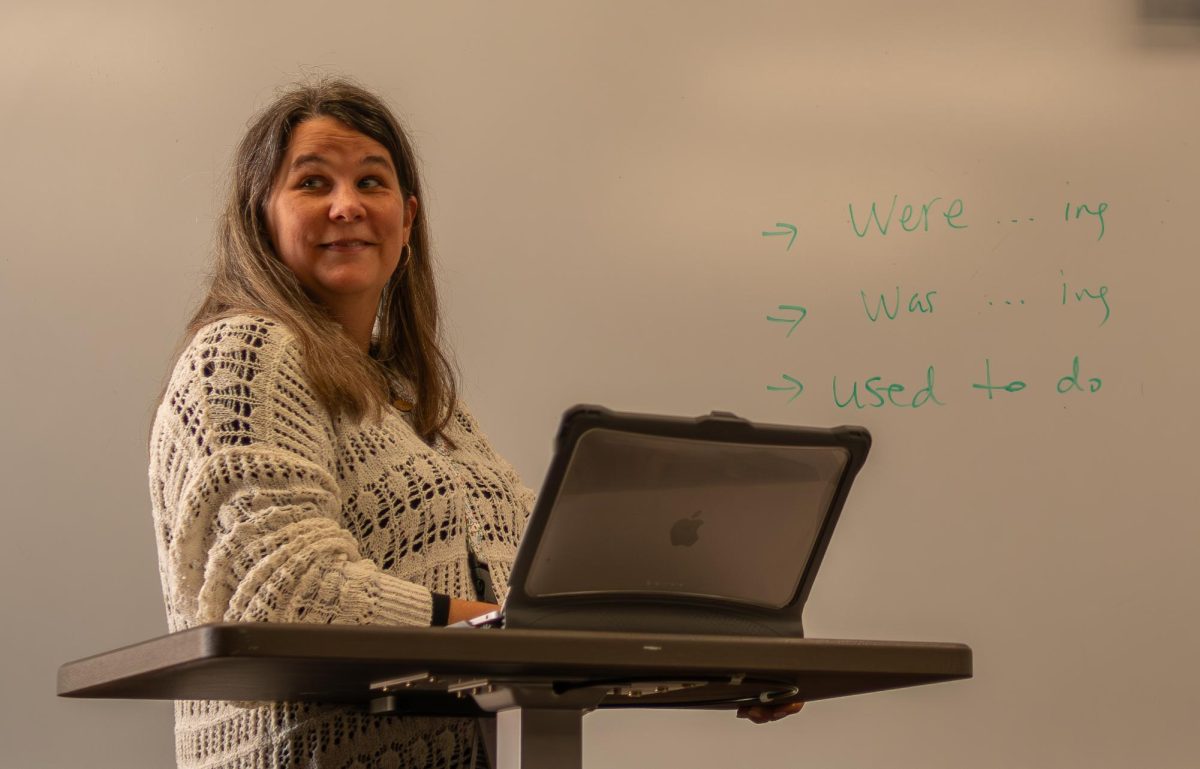

“Players won’t usually tell us that they think they’ve had a concussion, especially varsity players, because they don’t want to have to sit out,” said Dr. Daniel Schmoll, a family physician at Shawnee Mission Medical Center. “We usually look for dizziness, nausea, memory loss, some of the key symptoms. We ask other players if they saw the individual pass out briefly or do anything unusual.”

Schmoll also said that players often don’t realize the potential danger that is inherent with concussions. In North Carolina last year, two high school football players died from concussion-related symptoms. Each had returned to play within two days of being concussed. Fourteen high school football players died in 2008, according to the Annual Survey of Football Injury Research.

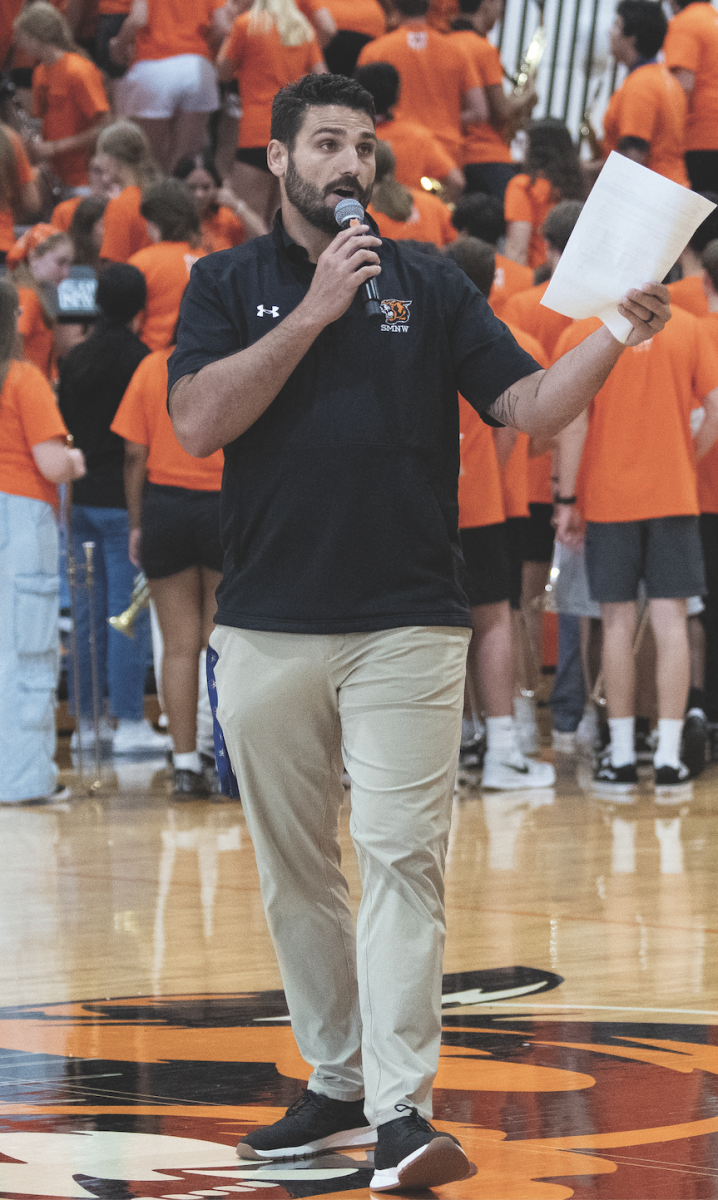

“You know, I would like to think that in my years of coaching, there are always two things I don’t mess around with: lightning and concussions,” varsity football coach Aaron Barnett said. “Head trauma, I think, is something where there can be some long-lasting effects.”

A study from the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, reported that 40.5 percent of high school players who suffer a concussion return to play prematurely, setting themselves up for serious health related repercussions later in life, namely depression, memory loss and early-developing dementia.

“The thing that kind of puts us coaches in a bind is a concussion isn’t something you cant just X-ray or look at. You have to rely on the player telling you about it,” Barnett said. “And what makes it tough is the fact that some kids may have a concussion and never say a word.”

In the event of a possibly concussed player, trainer Kodi Bauer is often the first on the scene.

“The first thing I ask them is if they have a headache, if they are dizzy, have blurry vision, ringing in the ears or any other symptoms. After those questions, I ask more cognitive questions like if they know where they are or what the score is,” Bauer said.

The problem is that players can deny most of these minor symptoms, such as headaches or dizziness. A report published by USNews.com indicated that only about 42 percent of high schools in the country have trainers, so even severe cases can go undiagnosed simply due to the lack of knowledge of stand-in trainers.

In some cases, the player may suffer a concussion unknowingly.

“It’s not uncommon to hear players say, ‘Oh, I just got my bell rung,’ or ‘That last one really got me,’ and then they just keep playing,” Bauer said. “Even if you only have a headache, and that’s the only symptom, that is technically a concussion, and it should be treated accordingly.”

The state of Washington has passed a law declaring that all athletes under the age of 18 suspected of having a concussion must have written consent from a doctor prior to returning to play. Coaches must receive concussion education, whether at seminars or through approved online material, and parents are required to sign off that they have read and understand the new requirements.

Though Kansas legislators have not proposed a bill similar to the one in Washington, Kansas State High School Activities Association guidelines support some of the same ideals of the law.

“Any athlete suspected of receiving a concussion is to be removed from the activity for the remainder of the event. The athlete should then not be allowed to return to sports until they have received written clearance from a physician,” said Brent Unruh, KSHSAA office manager and certified athletic trainer.

Legislative action is not the only way the issue of concussions is being dealt with. Equipment advancements are made every year, with new technology in the padding used in helmets becoming more effective.

Xenith, an equipment company that has emerged in the last couple of years, offers a new type of helmet that is supposed to reduce the likelihood of concussions. While most helmets use gel or a combination of foam and air for the interior padding of the helmet, the Xenith helmet uses highly durable thermoplastic polyurethane pads. The pads are designed to adapt to each hit the helmet receives and reduce the jarring effect on the brain, which is thought to be the main cause for concussions. The Xenith X1 was available for purchase to NW players this year, and 15 bought the $350 helmet.

“I think it works pretty well. I definitely can’t remember any huge headaches this year, as opposed to last year when I had a Riddell helmet,” senior Kosh Khan said.

While the Xenith allegedly reduces the risk of concussion, it is only available to players who are willing, or able, to pay for it. Even with this new technology, according to USNews.com, the number of concussions suffered each year— not just in football, but in all high school sports— continues to increase.

Football might be the first sport that comes to mind when head trauma is mentioned, but concussions can occur in almost any form of athletics. Sophomore Luke Schnefke suffered his sixth concussion last year in a collision with another player during basketball practice. Doctors told Schnefke that he should not continue playing contact sports. They told him if he suffered another concussion, he could begin having problems with his memory and basic motor skills.

“After my sixth concussion, I went to a neurologist and they did computer testing. They also said that the most concussions anybody they had seen was seven, and they are having memory problems,” Schnefke said.

That testing is known as the ImPACT test. The ImPACT test was developed at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and was first used in the NFL in the early 1990s. The test measures functions such as verbal memory, visual memory and reaction time.

“I couldn’t really tell if I was doing badly in the testing, but when the data was compared to other kids’ scores, you could tell,” Schnefke said. “It doesn’t really affect me on a day-to-day basis, but the doctors told me that if I get hit in the head again, I would be more likely to suffer another concussion.”

Another sport where head trauma can occur is soccer. In soccer, players often strike the ball with their head. While this might seem harmless, if a player hits the ball with his head incorrectly, if the ball simply has too much force behind it or if his or her head somehow collides with another player’s head, they could suffer a concussion.

“I wouldn’t say concussions are a huge problem in soccer, but it does happen,” soccer coach Todd Boren said. “Usually it happens when two players go up for a head-ball, and their heads collide.”

Concussions occur in virtually all sports: hockey, wrestling, basketball, UFC. Because many sports are played on a hard surface, all it takes is one slip and a player’s career could be over. And because there is no defense for simple clumsiness or for the occasional accident, concussions may just be a risk that players, parents and coaches have to live with.

“I don’t think that there is really anything that the coaches or players could do to try to prevent concussions from occurring. It really is just kind of a part of the game,” Bauer said.

Athletes in general continue to become more and more lethal to each other. As bench-presses increase, and 40-yard dash times continue to drop, collisions will only grow more violent, resulting in more injuries. While researchers work to develop more effective safety equipment, and coaches and legislators continue to try to protect athletes, in the end, the people who are most capable of protecting an athlete from permanent brain damage are the athletes themselves.

![With a flag in his hands, senior Marques Cook runs down the sidelines Nov 8 at SM North District Stadium. This was Cook’s last time running down the field with his teammates. “When you’re waving [the flag] in the air, you’re just thinking about getting hype,” Cook said. “Then when you run out with the team behind

you, the nerves and everything go away.”](https://smnw.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/dmitchell_vfb300_11.8_2-900x448.jpg)