Rating: 1/5

April 20, 2017

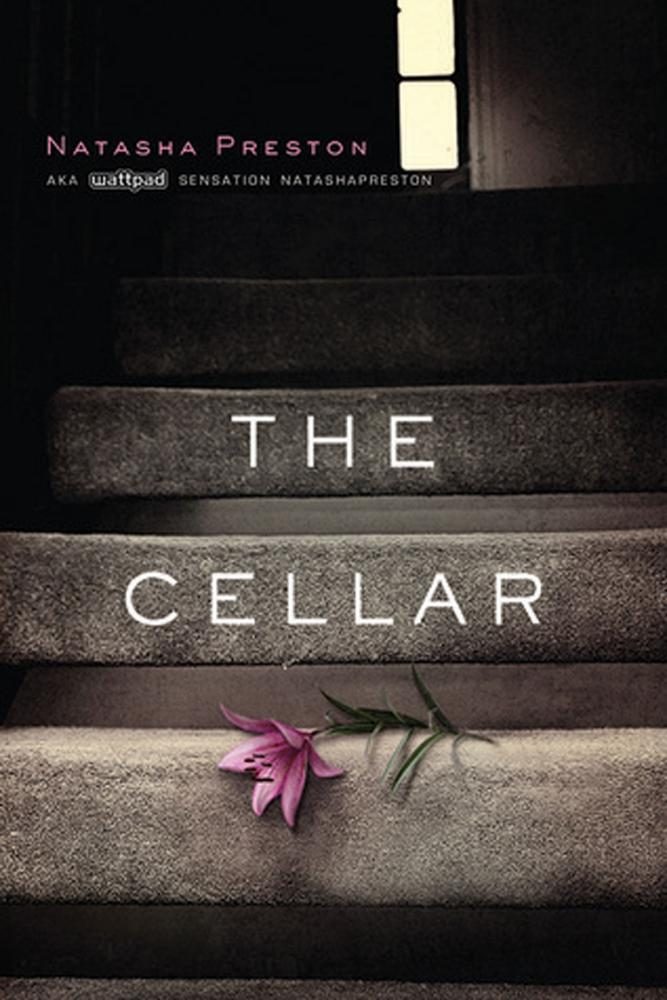

Natasha Preston’s The Cellar is reminiscent of an eleven year old’s first attempt at writing a story. The book begins quickly with a teen girl being pulled into a white van by a germaphobic middle-aged man, as if we’ve never seen that before.

First off, a warning — this novel was published after it received acclaim on Wattpad, a site where hopeful writers post their stories chapter by chapter. It didn’t take the usual route through publishers and editors.

That being said, this is a clearly unedited novel. There are countless plot holes, like the fact that the girls whined about not having weapons and Preston went into detail about the plastic vases in lieu of glass and weak, plastic chairs; yet, they cooked with metal pots and pans every day. There are numerous discrepancies, like the fact that the kidnapper’s eye color changes from blue to brown halfway through the novel. And, unfortunately, The Cellar has fallen victim to over-narration: main-character and narrator Summer is constantly talking, constantly voicing her opinions and thoughts about whatever is going on so much so that it’s impossible to enjoy the unfolding story.

Preston’s writing is forced at best. She tries to make up for lack of skill by stringing cliches together and inserting random snatches of description here and there. Example: “My blood turned to ice in my veins, and the pinch in my arms as his fingers dug into my skin stung. I looked down and saw his fingertips sink into my arm, making four craters in my skin.” Bad, bad, bad.

Summer’s is unrealistic and her narration is downright ridiculous. As a strange man emerges from his hiding place behind a tree, her thoughts are “What the heck? He was close enough that I could see the satisfied grin on his face and neat hair not affected by the wind. How much hairspray must he have used? If I weren’t freaked out, I would have asked what product he used because my hair never played fair.” Just, why? As she’s being dragged into a car by her kidnapper, Summer’s only thoughts are, “what the heck is he doing?” and “what the heck is wrong with him?”

This tame substitute for an expletive is quickly deemed pointless, as curse words are used plentifully throughout the rest of the novel. Nevertheless, the use of the word “heck” persists infuriatingly until the book’s end.

Summer is weak — not the strong nor sassy-to-a-fault girl we’ve grown to expect, since this describes basically every female protagonist ever. Preston did try to do something a little different, and there’s something to be said about that. But there’s a reason authors don’t write flimsy protagonists. Preston might’ve been trying to be relatable, but reading about a girl who solves her problems by crying, taking a shower, crying, wishing she was with her boyfriend and crying, some more is as frustrating as it is repetitive. Speaking of, Summer’s focus was entirely on her boyfriend — that seemed to be the only thing she missed. Not her family or, well, sunshine, for example. Preston lacks the intellectual capacity to explore the mindset of neither captor nor captive, and the emotional capacity to make you feel anything for either.

As the book went on, the writing style began to change. This turned out to be a good thing, as the last 100 pages or so Preston hits her stride. However, that couldn’t save this book, which can only be described as an unoriginal idea cushioned with beginner-level writing and absurd amounts of first person narration. I don’t recommend this book to anyone. Don’t waste your time or money on this half-hearted, forced attempt at writing.