No, but what are you?”

She says it as if wondering whether I am human or alien.

I played dumb at first — American. But I knew what she meant when she asked, what response she wanted.

She didn’t want to know where I was born.

“You mean what type of Asian I am?” I respond, toying with the hem of my jacket sleeve.

She smiles from across the grey Trailridge lunch table, her head tilted. It’s funny to her.

IOnce upon a time, it was funny to me, too.

In elementary school, it was funny to everyone.

Or at least, that was my perception, my formula for laughter.

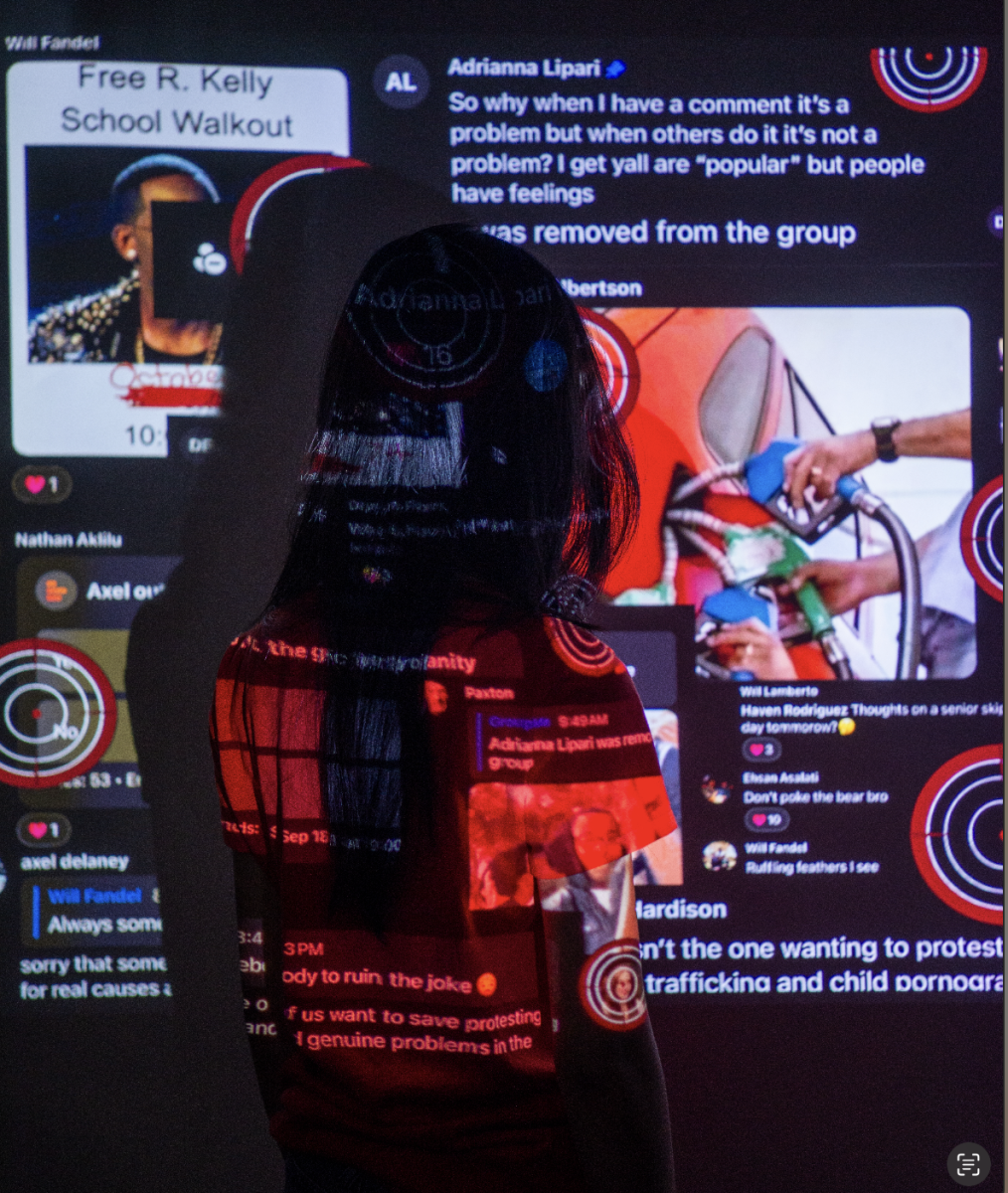

Let them tell you things like “Can you do my math homework?” and “Ew, what are you eating?” and “Where are you really from?” and occasionally even “So you’re not a real Asian,” when they learn specifically that you’re Filipina. Pull your eyes back, let them call you things like ching-chong.

It’s normal. You’re the weird one for reacting. And anyway, if you don’t do it yourself, someone else will. They’ll laugh either way.

It’s up to you: do you want to be in on the joke?

So you learn to make the jokes — “I ate dog for dinner,” or “My parents will beat me if I get a B.” Trade the pancit in your lunchbox for an Uncrustable, hot meals with rice in thermoses for Lunchables. Wear the trendier, more casual wear that everyone around you is wearing, instead of what your parents pick out for you.

The learned instinct to repress and conform is all-too common among Asian kids growing up in the U.S.

Too many Asian-Americans share the experience of laughing along to their ridicule. Many remember being the perpetual butt of the joke at the lunch table, or being treated as a homework answering machine, or being mixed up with Asian friends, or wishing that we were anything – white, hispanic (as lots are assumed to be) – other than what we were.

“I still have days when I wake up and I’m like, man, I wish I was a white girl,” Taiwanese junior Phoebe Baumgartel says. “Like, I wish I was, like, tan and blonde and blue eyed. I could get anything I wanted to.”

All while not making a fuss, lest you be deemed “sensitive.”

And then slowly, as we got older, something seemed to change.

Suddenly, it was cool.

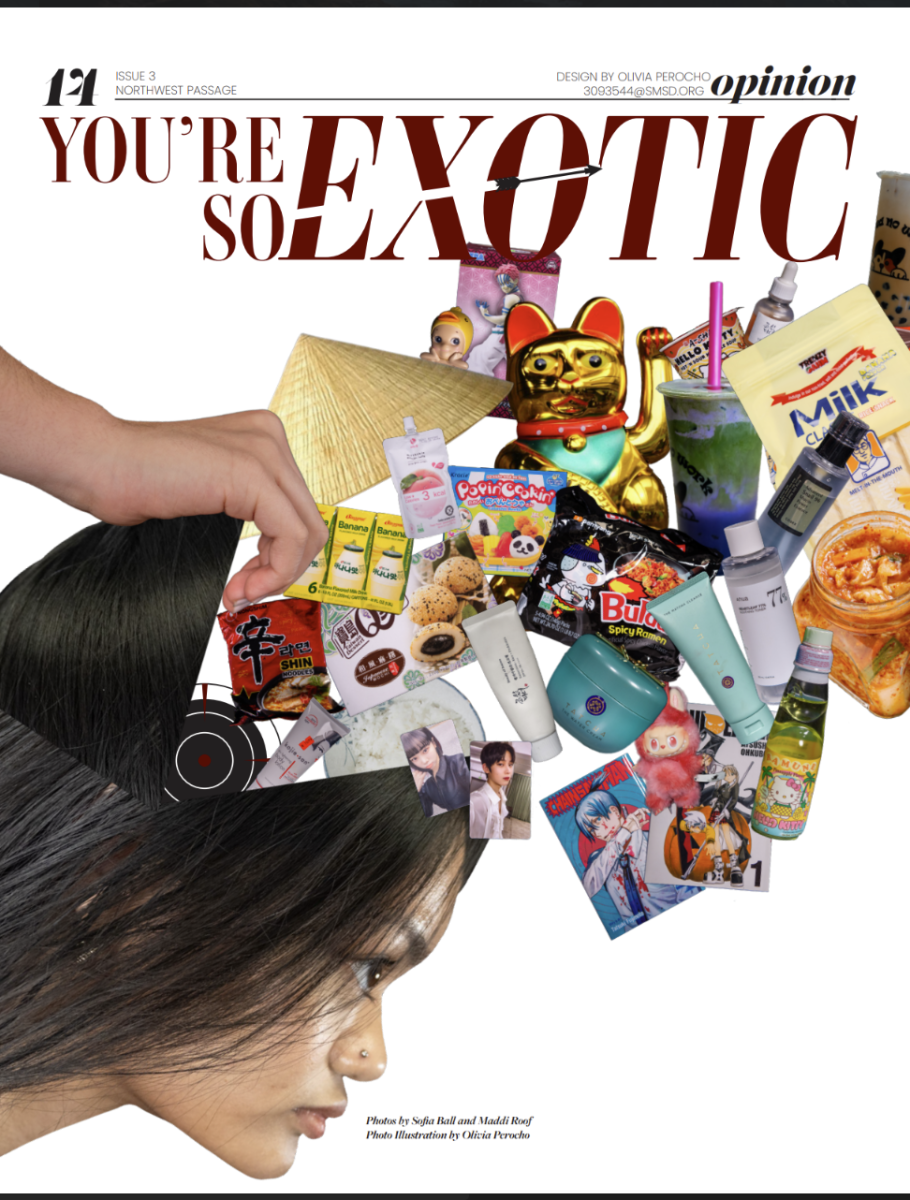

The same people who once guffawed at our lunch were now going out to eat Korean barbecue, or sushi, or pho, and stopping for a boba run on the way. K-pop and K-pop-inspired groups overtook their playlists. TikTok creators fawned over Korean skincare, Japanese haircare. Netflix “Continue Watching” bars overflowed with anime and Asian dramas. Matcha, an originally traditional Japanese drink, became the face of “performativity,” and little expensive collectibles popped up on fellow classmates’ phones and bags: Sonny Angel, Smiski, Labubu.

Now, instead of being outright derided, the approved parts of Asian culture and media are picked from and made into trends.

But how much better is that?

“A lot of people, I feel like, don’t really make an effort to learn about where, like, certain things originated from,” senior Jennie Lee says, “which is kind of taking away from the culture as a whole. I wouldn’t say it’s better than straight-up discrimination, it’s just different,”

Being Korean, she’s observed the same contrast between mockery and surface-level aestheticization of her culture. “I find it really ironic,” Lee says, “because the same people who are, like, drinking matcha, boba, and stuff like that were the same people that were, you know, mocking Asians. They want to, like, pick and choose, like, all the so-called good or bad parts of Asian culture.”

Often, the picking and choosing happens simultaneously with the now more latent disrespect.

Racism towards South and Central Asians, for example, is felt by many to not be taken seriously, online and in-person. “A lot of certain friend groups I hear make jokes about, like, India and Indian people,” junior Isabella Flores says. And Afghan senior Ehsan Asalati says “ get, like, the smarts side” of anti-Asian racism, but instead the “terrorist side.”

At the same time, aspects of East Asian culture are seen as aesthetic, or even fetishized and idealized. There are online instances of “Asian-fishing,” where people deliberately do their makeup so that they look plausibly Asian. Certain standards and expectations are set for Asian people, and they often buckle under the pressure of living up to them.

“I’ve definitely felt a pressure to conform to Asian beauty standards that you see in, like, Western media,” Lee says, such as those rampant within the K-pop industry.

Even outside the realm of beauty, stereotypes are still very alive and very felt. “People, like, want to come up to you and be like, oh, we’re just saying that you’re smart, you know, like, it’s a compliment,” Asalati says. “It in a way is not, though. You’re still just using, like, certain people to, you know, generalize to the whole population. And that isn’t fair even if you’re saying it in a positive way. Because, like, I mean, I wouldn’t see it as a positive.”

Anti-Asian racism is still felt by many to be normalized, even at Northwest. Filipino Freshman Rhia Perocho says that she feels like if you see “someone who’s, like, very obviously, like, Asian, going to be one of the first insults among people’s minds.”

One thing is common in both mockery and aestheticization: the objectification and reduction of Asian culture as a whole to a few digestible aspects.

The wave of Asian fixation is perhaps only the same disrespect repackaged in a Hello Kitty wrapper. And the Asian students of Northwest still feel the lingering effects of that disrespect, even if disgust has seemingly turned into adoration.

In the end, embracing Asian culture is a good thing. But it’s important to make sure we’re not unintentionally taking when we think we’re giving. And seeing other people’s acceptance – even if it is surface-level – makes it that much easier to take pride in the aspects still untouched by micro-trend frenzy.

I look up from the grey Trailridge lunch table. Her disrespect could be on purpose, or it could not. Either way, I’ve grown past the point of doing it to myself first.

“I’m Filipino.” I say it and I’m not ashamed.