Junior Husna Asalati’s feet pound the cracked pavement. Hard. The almost-90 degree heat is stifling. Thick droplets of sweat swim down Asalati’s neck. A stream of cars whoosh by on 67th street as she tries to keep her pace. The pack of cross country runners disappear around the corner.

Suddenly, Asalati is no longer trailing in the back.

She is running alone.

The rest of her team sports bright blue Hokas, Under Armor sports bras, and low ponytails. She’s decked head-to-toe in hers hot pink tracksuit zipped up at the collar, chunky black Asics and a black silky hijab.

She veers around the intersection and a question pops into her head.

The question she always gets asked. From the moment they see her hijab, a headscarf worn traditionally by Muslim women practicing modesty, down to her Asics. During warmups in the wrestling room. And before meets.

Why do you do it?

“You usually don’t see people like me doing cross country,” Asalati said. “Sometimes I don’t think people even know I’m part of the team.”

At first glance, Asalati is shy. On her way to one of the six AP classes she’s taking, her head is down. She knows she stands out in her hijab, so she wears baggy jeans, oversized hoodies and trendy sneakers, she says, to try and fit in.

Asalati was raised Muslim. She tries to pray five times a day — once in the morning and three or four times after school. Both of her parents are refugees from Afghanistan. Asalati is the only daughter. She isn’t allowed to date. She doesn’t eat meat. She was homeschooled from third grade up until high school, two years ago.

She doesn’t have much of an athletic background, and last year Asalati was struggling to make friends. She used to run with her dad when the weather was nice or occasionally on the creaky basement treadmill.

That’s what gave her brother Ehsan an idea.

“I felt really bad for her,” Ehsan said. “And I wanted to make an impact. Cross country seemed great. After all, it’s just running.”

Asalati refused to join cross country as a freshman and sophomore. She was too scared.

But Ehsan made it easier. He set up the physical needed at a local CVS, got his parents on board that it was a good idea, and talked with friends about looking out for her.

Asalati was still nervous, but the push helped.

“I thought maybe if somebody else saw me doing this and they’ve been scared to do it, they might feel different,” Asalati said.

Weeks later, on her first day of practice, Asalati stared wide eyed at the pool water with dread. It was pool running day. As the girls changed into their sports bras, and boys swim shirts, Asalati joined them in the pool wearing her trusty track suit. In the water, she reluctantly heaved her legs forward, trudging back and forth in the shallow end as her teammates synchronously ran in circles. The chlorinated water smacked against tiles as her anxiety surged. And Asalati’s layers were swiftly pulling her down like paper weights.

“It felt like I was drowning,” Asalati said.

She thought she was in pretty good shape already, but nothing could prepare her for that first practice, or the season ahead.

“Surely I thought someone would be slower than me,” Asalati said, beginning to laugh. “But no one was.”

She runs a 14 minute mile. That’s about double the time of a varsity runner.

She has a special route carved out by coaches that’s shorter, after she got lost the first time running with her teammates at practice.

They’ve had five races this year. Asalati has run two. She dresses differently for them.

“I know she was a little insecure about the outfit,” senior and c-team runner Lauren Snyder said. “She had to wear track pants. But everyone is supposed to wear these orange shorts. And they’re short. They’re really short. So she wore them over her pants. I didn’t think they looked bad. But if it were me, that would be hard.”

Sometimes people make jokes about it.

“Husna, your ankles are showing,” one girl said at practice, pointing to the gap between her white ankle socks and scrunched pants. “How scandalous.”

“Oh, yeah,” Husna said, a smile barely forming.

She brushes them off.

She knows the judgements strangers make about her. The prejudice held against Muslims. She’s used to standing out.

“They see the hijab first, and then me,” Asalati said. “I was scared that people would say something, especially at meets.”

Since the first grade she’s had to put up with bullying. Kids called her “terrorist” from the swingsets or said she had cancer. One boy was dared by a group of girls to punch her in the stomach at recess. Another boy tried choking her out as they waited in line to charge their iPads — for Asalati, and her parents, this was the last straw. So they took her out of public school.

Asalati has always loved wearing her hijab. But today she feels more confident wearing it. She even forgets to take it off at home. And she handwashes it with detergent every night before bed.

“It makes me feel more beautiful,” Asalati said.

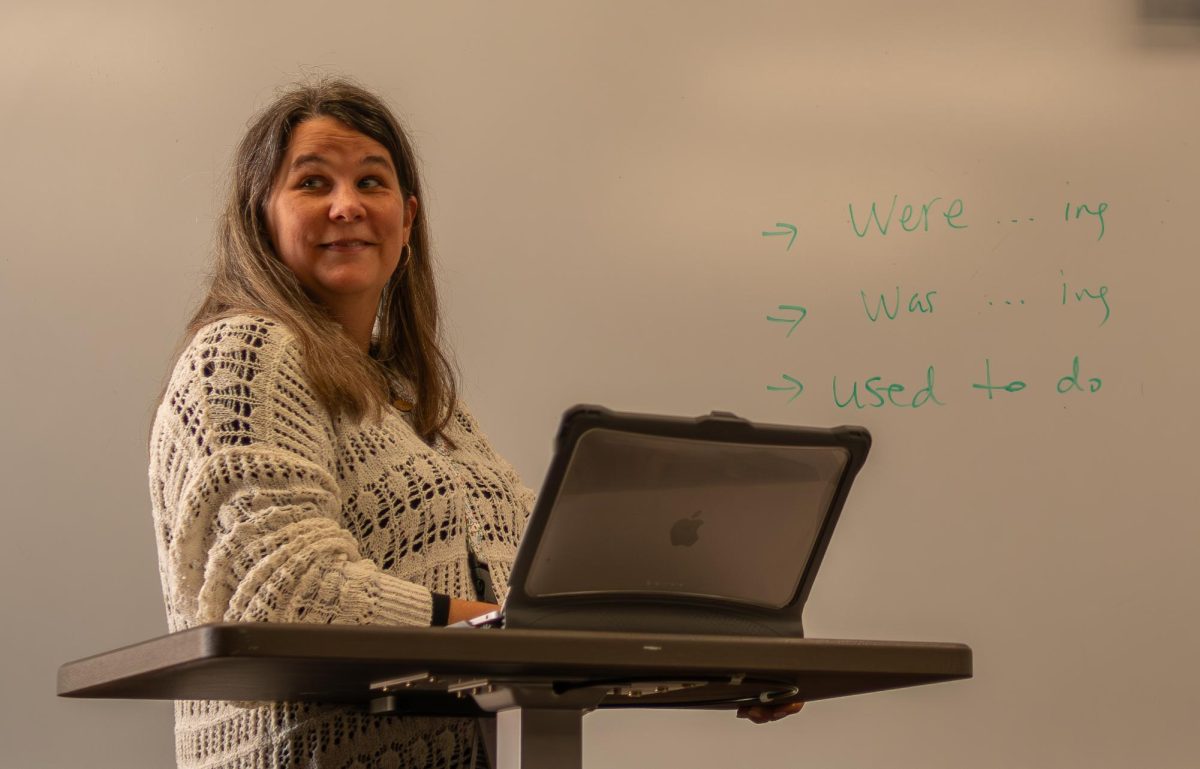

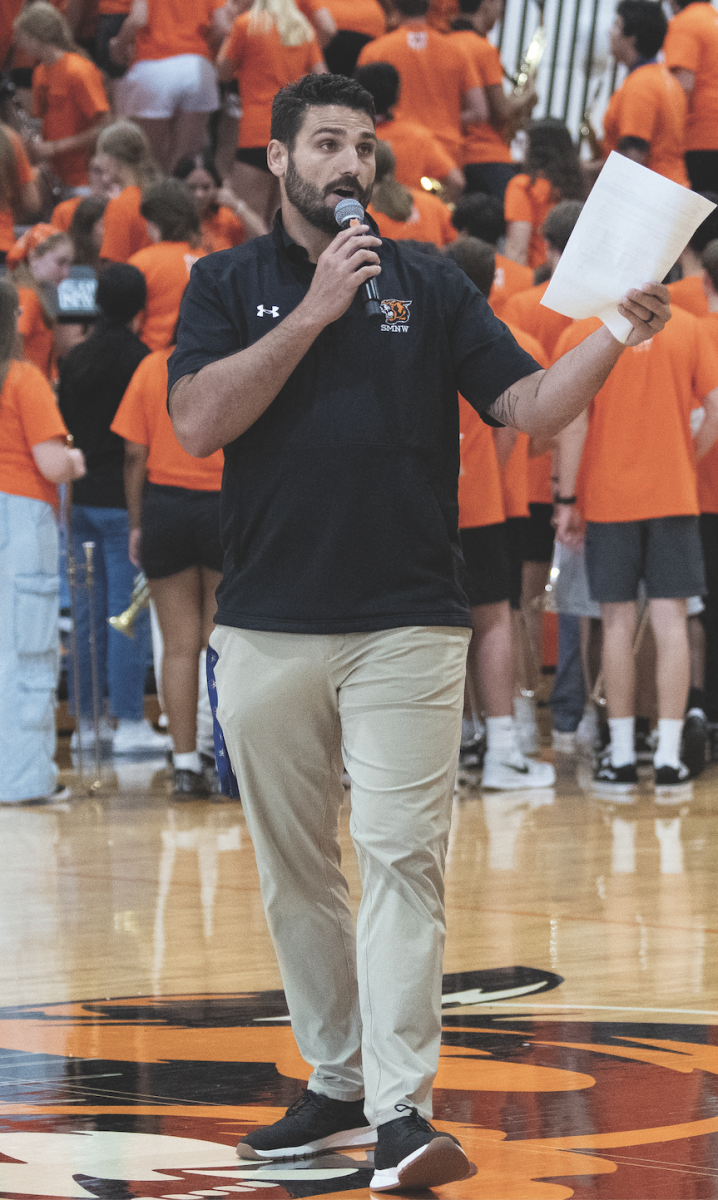

She was nervous of how it would make her stand out on the team. In seven years of coaching cross country, Dr. Johnny Winston says he’s never seen another student on the team run while wearing a hijab.

Asalati believes the challenges she faces are a gift from God. It’s what’s gotten her through life. And the cross country season.

“It means he’s bringing me closer to Him,” Asalati said.

Two weeks ago, her coaches had her take a break from running to rest her shins, which were in excruciating pain. Asalati spent practices in the weight room using the elliptical machine, doing core exercises and other strength training.

“I’d rather be running,” Asalati said. “But I don’t wanna be in more pain.”

Asalati hopes to heal completely, compete in more races and run the full three miles without stopping.

“I’m really hoping she has that moment where she pushes through and gets to see some success for all her effort,” Winston said. “Right now we’re just trying to help her build without breaking.”

Asalati’s mile time has hardly changed since the season’s start. It’s her first and last year on the team since she’ll be graduating a year early. She hasn’t hit a PR. Or medalled.

Even now, none of her coaches can pronounce her name right.

“I don’t even feel like correcting them anymore,” Asalati said.

But to the surprise of coaches, runners and anyone who might’ve passed her by, Asalati has shown up to every practice, changed into her tracksuit and faced the weight room alone.

“What’s honestly amazing is that she’s never brought up quitting at all,” said Ehsan, who picks her up every day from practice around 4 p.m. “And I feel like if there’s anyone she would bring it up to, it’s me.”

She’s run in the pool when it felt like she was drowning. She’s attended every pasta dinner — they make a special batch of alfredo sauce since she doesn’t eat meat. She’s taken to her route down 67th street, her hijab flapping in the wind, on days when it was as if every passing car was watching her when she didn’t feel like part of the team.

Asalati did it anyway.

“She could have gone out and picked up running on her own,” Winston said. “But she chose to be on the cross country team.”

There will be people who don’t understand why.

Now she has people to sit with at lunch. And to text after school. A community.

Asalati has come to peace with the fact that she’s not on cross country for awards, or recognition. That she may never run with the pack. Or run a mile under 10 minutes. She’s there so that she can prove something to herself. And no one else.

But for her, it really is pretty simple.

“I love running,” Husna said. “I know what it’s like to feel scared. Like I’m the only one who’s different. But no one really cares. That’s what I tell myself.”