For most people in 2025, the divide between Democrats and Republicans is becoming harder to ignore.

According to Gallup, a global analytics firm, the percentage of Americans identifying as moderate, or the middle ground, has decreased from an average of 43% to 34% in 2024, with Americans more likely to side strongly with liberal or conservative ideology. A poll by Gallup also states that 57% of adults in the U.S. avoid sharing their political beliefs for fear of facing harassment or poor treatment. In a podcast episode of “On the Media,” Lily Mason, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University, said about 80% of Democrats and Republicans think the other party is a threat, with about 40% to 50% of those people thinking the other group is “downright evil.”

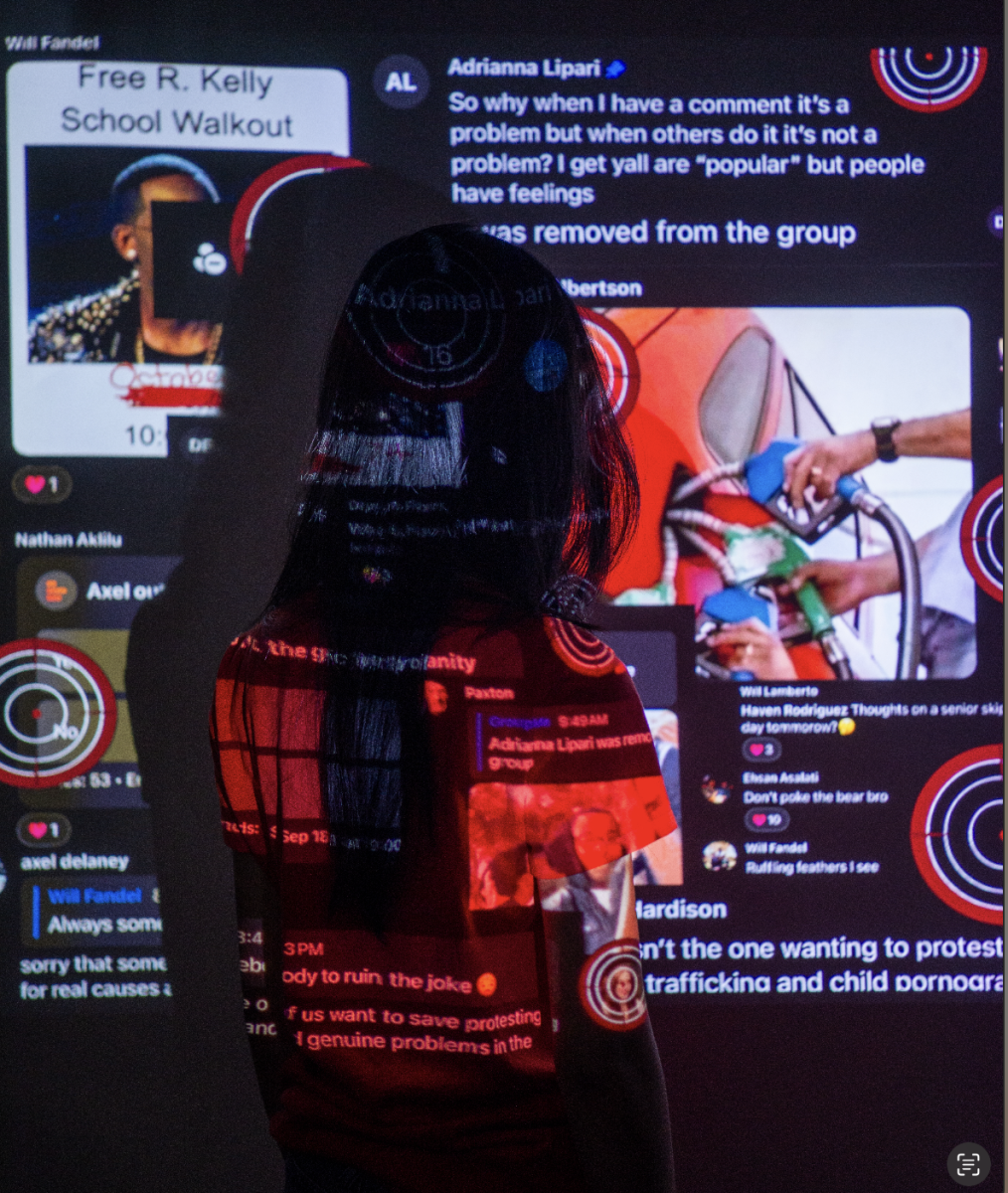

Because of this divide, fewer people feel comfortable sharing or talking about politics, including students at Shawnee Mission Northwest.

“No, I definitely don’t feel accepted,” Republican sophomore Kylee Hook said. “I feel like if I talk about my beliefs, more people just aren’t going to agree with me.”

Nearly 10 students declined to be interviewed for this story in fear of their political beliefs being on record.

“I sometimes feel fear that if I truly say what I think, then people won’t see me the right way, or like, see me the same way,” sophomore Gus O’Mally said.

For some students, this insecurity stems from experience.

Last year, during lunch in the cafeteria, sophomore Ren Conner sat at one of the long tables while conversations erupted over him. When the topic of politics came up, Conner mentioned he did not agree with something — then someone at the table suddenly called him a slur regarding his sexuality.

“I felt singled out,” Conner said, “Like no one was standing up for me.”

Since then, Conner has been more hesitant to share his political opinions at school in fear that it would happen again.

Even though many students at Northwest share Conner’s experience, there are spaces designated for having civil political discussions and debates, such as clubs like Young Democrats and Young Republicans.

Young Republicans meet in room 124 every other Friday morning. There, conservative students talk about current events and how they relate to the Republican party’s beliefs. This includes national news like Charlie Kirk’s assassination, to international issues such as the military crackdown in Nepal. Their first meeting was on September 19.

“I try to make sure, as a sponsor, that it’s not just focusing on what the conservative position is on key issues,” history teacher and sponsor Todd Boren said.

Young Democrats have not yet had their first meeting. President of Young Democrats, senior Malaina Perry said they’ve experienced a decline in attendance due to lack of activity in the club. She wants to change that through consistent social media posts, hanging signs around school, and sending out more GroupMe messages.

“It’s not a commitment,” Perry said. “You can come to one meeting or three. And if you aren’t interested, that’s okay.”

Regardless of what beliefs a student identifies with, or how politically active they are, club leaders say meetings are open to everyone.

“The main idea is that we have a safe environment for people to ask questions and share what you’ve experienced,” Perry said. “You don’t have to be registered or specifically want to be a Democrat or liberal.”

The club attempts to help students develop political views and get students involved in politics.

“We are hoping to have action steps where the students will be able to get involved very actively in the political system,” band teacher and Young Democrats sponsor Brett Eichman said.

Before Eichman, history teacher Rebecca Anthony was the sponsor for Young Democrats from 2010 until last year. She quit because of fear of her involvement in Young Democrats affecting her daughter.

“My daughter is in 7th grade and she will be in a few years,” Anthony said. “I don’t want anyone giving her grief for something I do with a club.”

Political division doesn’t always show itself; instead, it lingers quietly, in conversations between friends, classroom debates, and meetings in clubs that struggle to gain momentum. As politics becomes more present in students’ lives, the division remains in some ways that are difficult to address. Finding a political common ground isn’t just a challenge. It’s a conversation students are too scared to start.

“You don’t want to be left out or bullied for your beliefs, so it’s easier to just hide it,” Hook said.