The sun shot rays of light on every blade of grass.

Sweating. With the handmade shed in the left corner and the tree, which turned yellow and orange in the light, stood in my backyard.

I sip pink lemonade and watch a cute brown-haired boy. Older. Wearing navy trousers. A sweater that read Chelsea. He practiced swordsmanship across from me. I’m seven years old, daydreaming about the main character from a movie I couldn’t finish because of a power outage.

I’ve never seen a fencer. I’d never visited Chelsea in real life.

The boy’s not real. It’s all in my head.

***

Daydreaming wasn’t dangerous then. I wasn’t crying or lost. “Am I a good friend?” I asked Peter Pan one night. He smiled and showed me fairies until dawn. It felt like a superpower.

Everyone daydreams. Future husbands. Weddings. First kisses.

“I like to imagine the neckline of my dress before I walk down the aisle,” my friend Charlotte said while brushing mascara on her eyelashes, preparing for our first middle school dance.

My friends nod as Stella says she wants a mermaid dress and six-inch heels.

I can relate, sure. I see images in my mind, sure. I think about my future, sure.

But my daydreams aren’t the same as their fantasies.

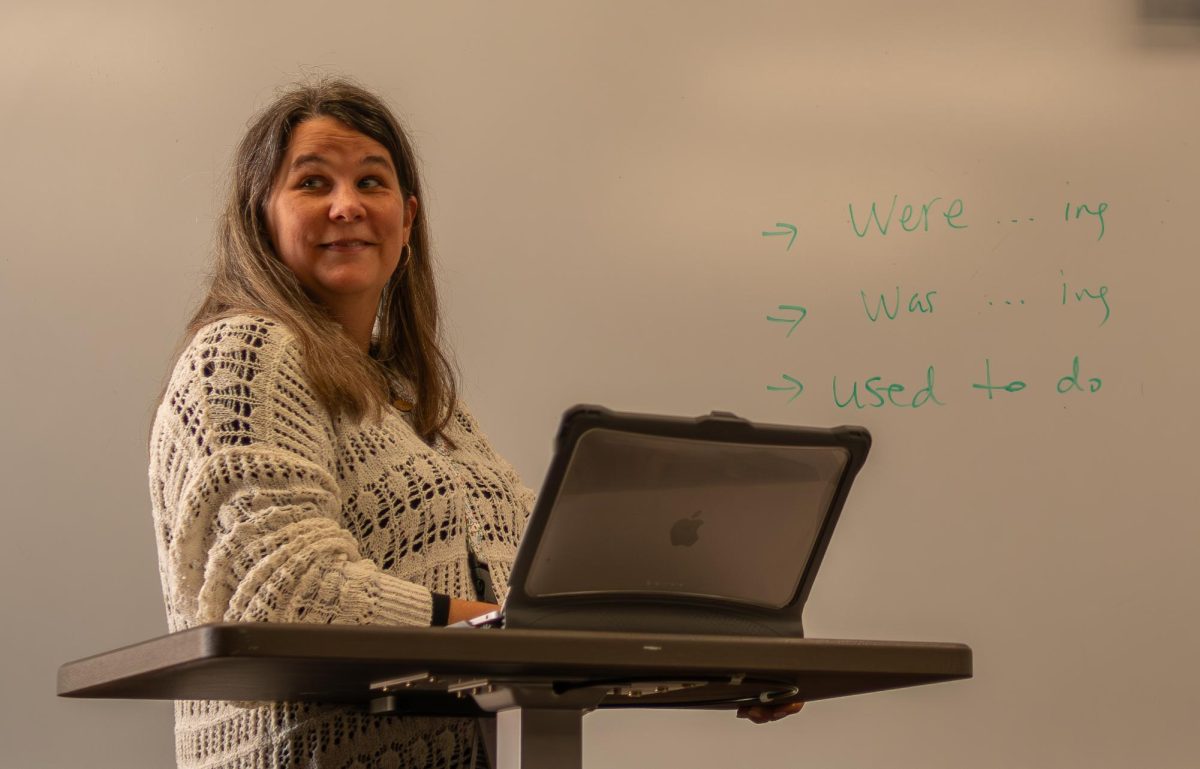

Ironically, my parents sent me to a therapist named Chelsea.

***

I spend the most time in my driveway.

Purple kickball in my hand. The ball hits the cracked pavement.

Dogs. Babies. Runners. They all see me quickly snap out of my daydreams as they walk by. They see my lips move, unaware of what I’m saying.

I wave. They wave back.

***

In fourth grade, I started daydreaming every day.

Sometimes when I get in trouble, my parents won’t let me go to the driveway. I get snappy and fidgety when I can’t find the time to allow the thoughts and scenes to flow through my head.

Somehow, I’d find time to get coffee with my characters or console them on the breakups I made them have.

Getting ready in the morning, I don’t see myself. I see the face of someone else, doing something else.

At Christmas, I thought about how the boy who was older and wore navy trousers and a sweater that read Chelsea would react to unboxing the vinyl I had just opened.

Would he sing along?

Smile slightly and pretend to be grateful?

Or would he realize someone was thinking about him?

Dreaming again…and again…and again…

My daydreams aren’t just harmless flights of fancy. I cry when my characters cry, laugh when they laugh. All in private.

“We thought you’d grow out of it. Going to the driveway,” my mom said over pasta.

My dad nodded. “You didn’t.” He raised an eyebrow.

I rehearse the same scenes over and over, slightly tweaking the conversations.

“She said hello,” I say. First, as a question.

“She said hello,” I say. Now, as a statement.

“She said hello,” I say, perfecting the tone. Fireflies danced through my hair. But is it really my hair?

Age 12, I’m walking through the block party at the corner of my street. A lady stops me.

“I’ve seen you outside your house.” Her lipstick shines brightly. “I’m so proud of you for spending time outside. Makes me so happy to see young people off their phones.” She hands me a bowl of her homemade pasta salad.

“You’re the girl who bounces a ball outside on her driveway,” she chuckles.

I guess that’s who I am.

***

Daydreaming got too much in seventh grade.

The day my mom drove me home after Chelsea diagnosed me. “…Baby One More Time” by Britney Spears played on the radio.

Once we’re home, I open my bedroom door, pick out the darkest fabric I can find — dark purple, left over from a pillow I made — and cut it into a strip, covering my eyes with the fabric and tie the blindfold as tightly as possible.

All I can see…nothing.

Perfect.

Maybe, just maybe, I can stop daydreaming if I stop seeing. One of the issues with daydreams is that they happen in your mind, not your eyes.

A blindfold isn’t gonna do anything.

But I can try.

I searched my room for a journal and a pen. Flipping to the back page, I used my best blind handwriting and wrote a letter to each and every one of my characters, feeling around the paper with my fingers as a guide.

Telling my characters goodbye. Telling them they have to leave. Telling them they’re causing me more harm than good.

Tears leak out from under the fabric.

***

The reason maladaptive daydreaming is called a disorder?

Because the dreaming never really leaves.

Saying goodbye doesn’t make daydreams go away because they aren’t real. My daydreams don’t respond like actual humans.

Maladaptive daydreaming will always be a part of me. There’s no real medication. I’ve come to terms with this condition and I will always have my own passport to my daydreams. But maybe I don’t want to go on vacation.

At 14 years old, I sit down on a bus, turn on my headphones, and look out the window. I see the boy who wore navy trousers and a sweater that read Chelsea.

Now he’s the same age as me. Lounging in a chair — offering me a smile and a wave — just telling me hello.