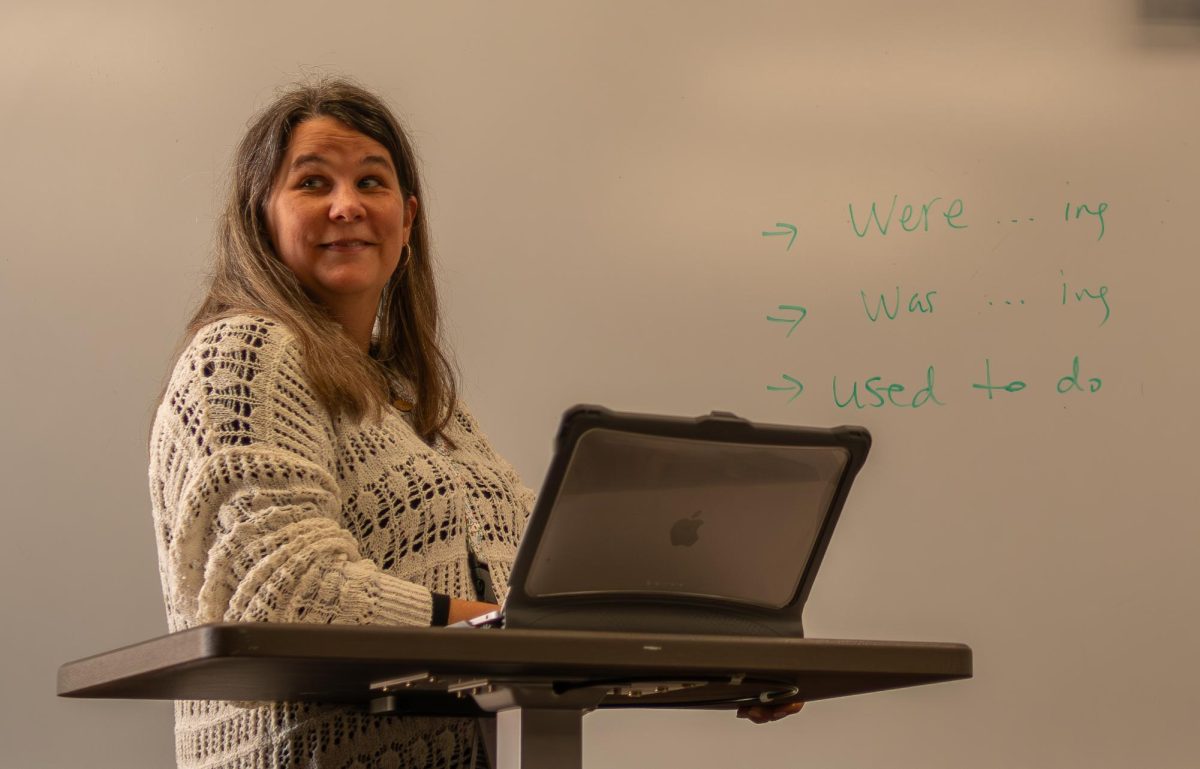

Freshman world regional studies teacher Stacey Delay struggles to retain the attention of her class. A group of boys sit clustered in the middle, and no matter how loud she speaks, what she says or what she shows on the board, they simply will not listen.

A male teacher walks into room 14 to discuss sophomore year social studies options. The second he begins to speak, Delay notices the class’ volume ease. Macbooks closed. The male students who, just seconds ago weren’t even listening, sit up straight.

“The way that the attention in the room shifted toward him so effortlessly,” Delay said. “That really was the moment where I was like, ‘Oh. This is very much a thing.’”

Delay’s experience isn’t unique. Many female teachers at Northwest notice the same patterns of students challenging their authority, responding differently to male teachers, having to fight for respect that is guaranteed to their male counterparts and being expected to be a nurturing figure in the classroom.

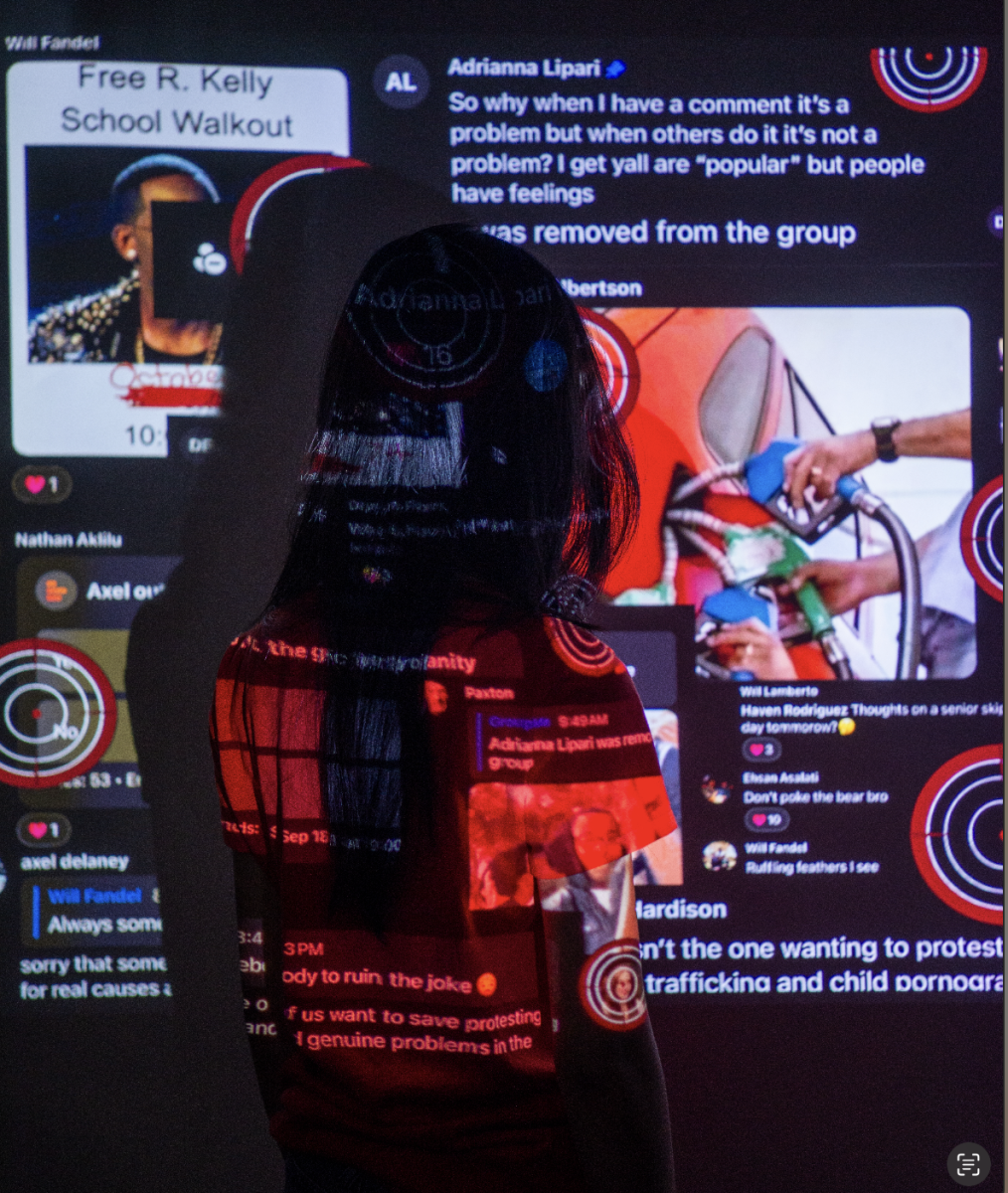

In an Instagram poll by the Northwest Passage, 60% of student respondents said that they noticed a difference between the treatment of female and male teachers.

“I’ve definitely noticed it,” junior Zaiden Robinson said. “People say things about my female teachers they definitely wouldn’t say about men.”

In a study of the effect of online misogyny on treatment of female teachers in Australia published by Stephanie Wescott, Steven Roberts & Xuenan Zhao (2024), they “suggest boys’ sexist practices towards their teachers and girl peers forms part of a strategy of gender inequality legitimization, stabilizing and reinvigorating a regressive ‘male supremacy’.” In other words, because of the rise of online misogyny, male students are becoming more disrespectful of female teachers and peers in school.

“Adolescence,” a British miniseries that follows a 13-year-old boy accused of murdering his female classmate, started airing on Netflix on March 13. The show has been well received by both critics and fans. It earned a 99% Rotten Tomatoes score, and a voucher from Anneliese Midgley, member of the British Parliament, who said that the show should be “screen in Parliament and schools,” to “help counter toxic misogyny.”

Among multiple themes depicted in the series, the disrespect toward the forensic psychologist, a woman assigned to uncover Jamie’s view towards women, has resonated with audiences. Following the effects of misogynistic internet atmospheres, Jamie is left angry and distrustful of females around him, and completely unwilling to listen to women in any authoritative or leadership role.

For Delay, being a female teacher is a push and pull between avocation and authority. She constantly faces the expectation to be nurturing instead of authoritative.

“There’s an expectation that we’re supposed to take care of everyone,” Delay said. “We have to waste all this time by apologizing for asking for what we need.”

As a woman in a leadership role, Delay encourages her female students to not say unnecessary “sorrys,” and to not let disrespect go in the name of being undifficult. She doesn’t let disrespect towards her or to students on the basis of gender go unnoticed.

“If you’re a male teacher, I think that you have more credit just by the virtue of being a male,” Delay said. “And for a female teacher, and for a female intellectual, it feels like banging your head against the wall.”

Delay isn’t alone in noticing these patterns.

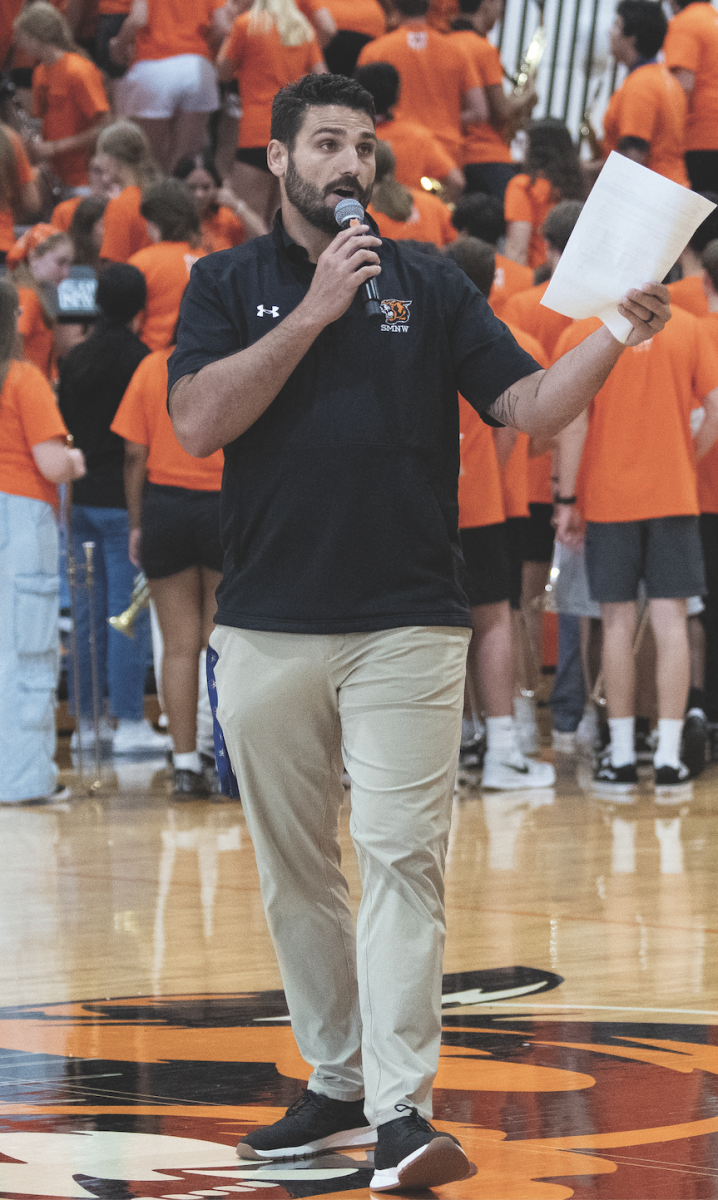

Rebecca Anthony has been a social studies teacher at Northwest for 17 years, and has experienced first hand the double standards between male and female teachers’ treatment.

“It’s like, ‘Oh, you’re a female teacher. So you should be nice nurturing,’” Anthony said. “And I feel like students, male and female, let male teachers get away with saying things that people’s jaws would be on the floor if I said.”

A few years ago, a group of male students in Anthony’s AP US History class played clips of Andrew Tate — a podcaster known infamously for misogynistic messaging and sexual assault — directly in front of her.

She knew they wouldn’t do that in front of a male teacher.

Anthony has also noticed differences in responses between female and male students when she tells them to do something.

“If I were to be like, ‘Hey guys, can we please close our computers?’ I’d say most of the time, female student is pretty likely to do that,” Anthony said. “Whereas, often, when I ask male students, ‘Hey, can we not be watching basketball games?’ they hear me, and they’re like, ‘No.’”

“The only assumption I can make is that, just as any sort of authority figure, they don’t take females seriously.”