On March 20, president Donald Trump signed an executive order instructing Secretary of Education Linda McMahon to begin dismantling the Department of Education.

The order, “Improving Education Outcomes by Empowering Parents, States, and Communities,” outlines alleged inefficiencies and suspected wrongdoings of the Dep. of Education itself. Trump stated that the department has not only done nothing to improve student outcomes like graduation rates and test scores, but also wastes billions of dollars in taxpayer money, creating regulations that “redirect resources toward complying with ideological initiatives, which diverts staff time and attention from schools’ primary role of teaching.”

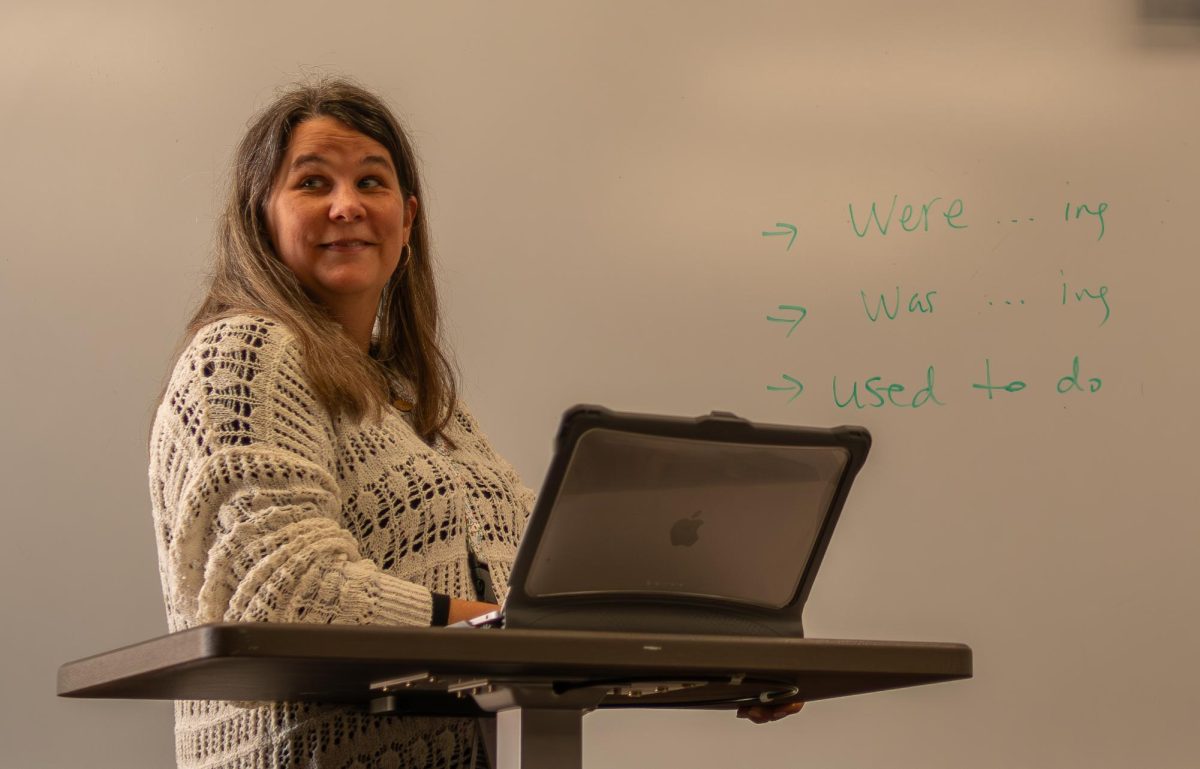

Government teacher Christin LaMourie expressed frustration at what these executive actions symbolize in regards to how educators are already being treated today.

“It feels like an attack on teachers and public education,” LaMourie said. “There’s a lot of people that dedicate their working lives trying to make the future better for students.”

According to an Instagram poll posted by the Northwest Passage, 71% of students who responded were very concerned about Trump’s announcement to dismantle the Dep. of Education, and 17% were unsure.

“What I’m worried about is that you get rid of funding it easier for people going to college with scholarships and student loan forgiveness,” senior Eli Marvine said. “I filled out FAFSA. And I’ve seen a lot of people posting their opinions online who rely on FAFSA to pay for their college.”

On March 11, officials said the Dep. of Education would be cutting half of its staff. This also resulted in the termination of contracts dedicated to maintaining the Free Application For Student Aid, or FAFSA website, and helping users navigate complicated forms and answering questions.

Marvine said he believes that these barriers to seeking and receiving financial aid will discourage students from seeking higher education altogether, and this will end up having a negative cascading effect on the school system.

“If right and the Dept. of Education was bloated, then you would never see a difference,” LaMourie said. “Because they would still be able to fulfill their function without those extra workers. If he’s wrong, then it’s a matter of, ‘Are those people working overtime? Is one person doing the job of three people?’ And how long can they sustain that?”

Trump has begun distributing functions of the Dep. of Education to other federal agencies. On March 21, Trump announced his plan of moving all student loan portfolios to the Small Business Administration. This transfer, which has instilled confusion in financial aid advisers on college campuses across the nation, will be effective immediately.

The federal government provides Kansas with 16.6% of its educational funding, according to the Education Data Initiative. Kansas K-12 schools receive $777.8 million, or $1,594 per student from the federal government, whereas state and local funding combined averages $8,379 per student.

Extracting federal funding that directly supports students with disabilities and poor K-12 schools has the potential to directly impact Northwest.

LaMourie said that the state of Kansas already doesn’t fulfill their obligation of providing enough fiscal support to help students with disabilities.

“Legally, you have to serve those students with special needs,” Lamourie said. “So you have to make up those costs from somewhere. If you’re losing that federal funding from the Dep. of Education, that’s even more money being pulled from general funds, which means less money for everyone.”

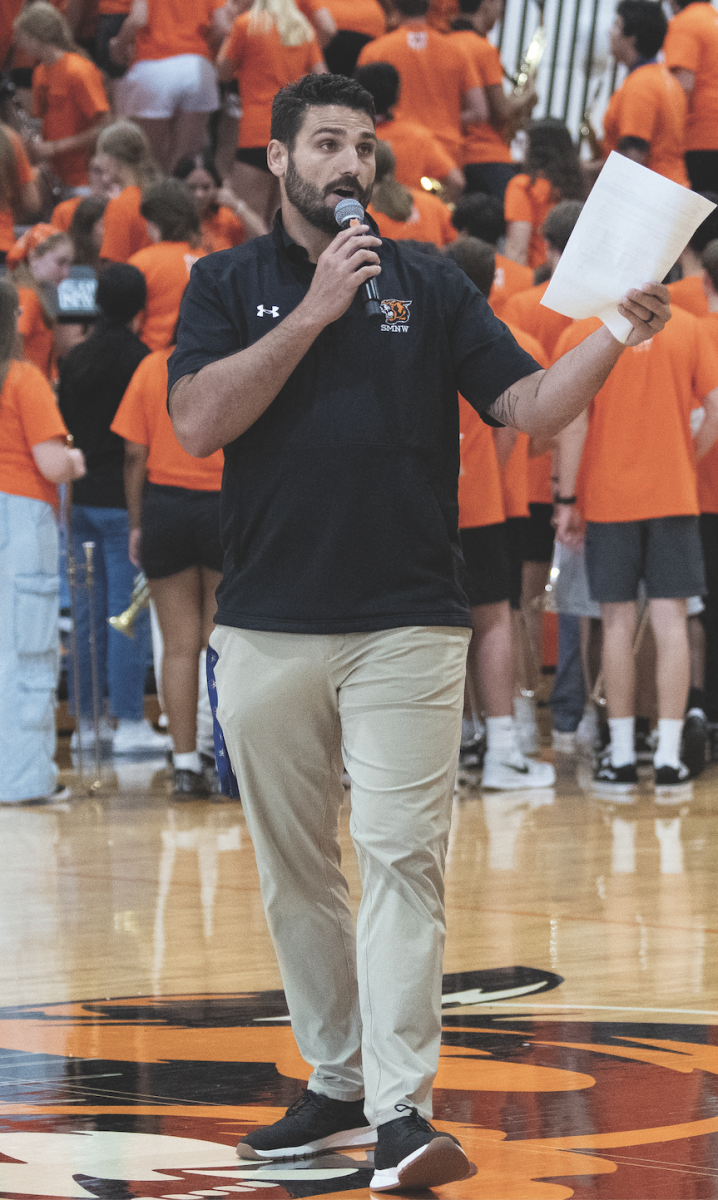

Without federal guidelines on how to disperse those funds, states would have the deciding power on where this money goes. Teachers like Matthew Wolfe have pointed out how historically, certain states have weaponized funding in a way that revokes civil rights from certain groups or individuals.

“If you start putting that funding back to the states maybe we see it pop up again,” Wolfe said.

This order, and Trump’s actions facing heavy scrutiny and legal intervention regarding the Dep. of Education have complex implications. No one is really sure which schools will be impacted, where or how. Some teachers have said the only thing they can do now is “wait and see.”

“Maybe I should be more worried,” Wolfe said. “But that can’t change anything.”