*Names of students were changed to protect their identities

They had come.

Looking through the peephole on her front door, sophomore Rosa Hernandez was mortified. She went to the porch window. There were four of them, four U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (I.C.E.) agents.

They were going around her neighborhood, knocking on every door.

Finally, they had gotten to hers.

“We didn’t move a muscle,” Hernandez said.

They wore white button up shirts with green camo pants, two in the back carried big guns. They pounded on the door again.

Hernandez told her family to turn off the lights and hide upstairs. The house was silent — any noise could give them away.

Her parents and brother, all undocumented immigrants, couldn’t be caught, they couldn’t go back to Mexico. She didn’t want to lose them.

Tears welled up in Hernandez’s eyes.

Not long after, those agents moved on to the house next door.

“I couldn’t stop crying that day,” Hernandez said.

Ever since President Donald Trump was sworn in to his second term on Jan. 20, his administration has been trying to radically change U.S. immigration policy, following up on campaign promises of securing the southern border, implementing mass deportations and ending birthright citizenship.

Students at Northwest, 23% of which are hispanic, and 6.8% multiracial according to the Kansas State Department of Education, are starting to feel the effects.

In the Executive Order “Protecting The American People Against Invasion,” which Trump signed on his first day in office, Trump wrote: “Many of these aliens unlawfully within the United States present significant threats to national security and public safety, committing vile and heinous acts against innocent Americans.”

Certain attempts by the Trump administration to carry out these immigration policies have already been blocked by district, state and federal courts. In February, judges blocked an order from the Trump administration to end birthright citizenship, citing a violation of the 14th amendment.

School district officials and administrators are cultivating new procedures to protect students. Social workers have met with students to cope with anxiety attacks in school. Teachers are reading off rights to their students in case they ever come into contact with I.C.E..

Even so, there are undocumented students who live in fear.

“I think here is the only place we’ll be okay, so scared or not, I mean, we have to stay,” Hernandez said.

During his first week in office, the Trump administration’s Department of Homeland Security (DHS) ended the practice of barring I.C.E. and border patrol agents from entering “sensitive areas” like churches, courthouses, hospitals and schools. According to acting DHS secretary, Benjamine Huffman, they have one motive:

“Catch criminal aliens — including murderers and rapists — who have illegally come into our country,” Huffman said. “Criminals will no longer be able to hide in America’s schools and churches to avoid arrest.”

It begs the questions: Can I.C.E enter a school like Shawnee Mission Northwest at any time? And, if so, are students safe?

According to the 2024 Kansas Statute, state law enforcement can only detain people for crimes they’ve committed, and if that criminal is an undocumented immigrant, I.C.E would handle the situation from there. The police don’t have the authority to enforce federal laws — immigration is a federal issue. According to Corporal Vivian Lozano of the Shawnee Police Department, they are awaiting further instruction from Kansas Governor Laura Kelly’s office.

In April of 2017, the Board of Education passed a resolution stating that immigration officials must come to the superintendent’s office before entering a Shawnee Mission school or district building. It also prohibits district officials from asking a student about their legal status and sharing that information.

The district’s Investigations and Interrogation policy prevents I.C.E. agents from entering SMSD schools and conducting student investigations, searches or arrests without producing a valid warrant, parent or guardian permission or cause for an emergency.

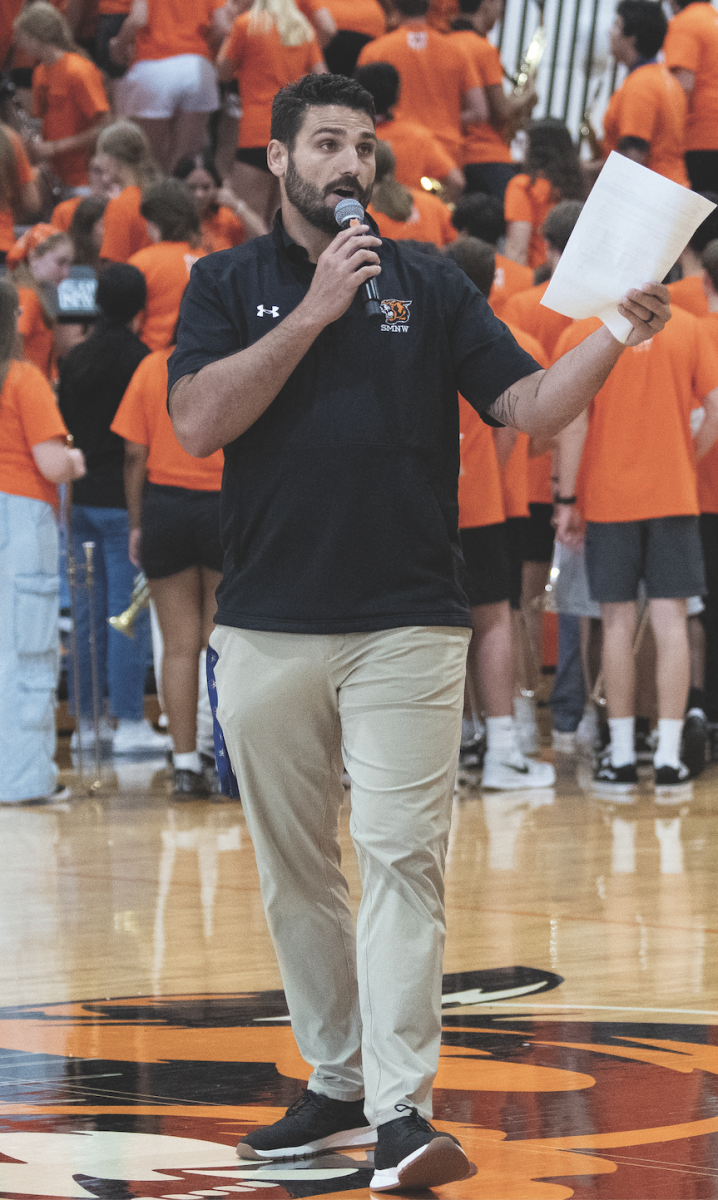

“We believe a safe and inviting environment would be disrupted by the presence of active immigration enforcement occurring at school,” Shawnee Mission School District superintendent Michael Schumacher said. “School is not the place to do that, right? It’s not good for the child. It’s not good for the other children.”

Schumacher said that the district’s Chief of Police Mark Schmidt, who has connections with local authorities, made remarks about I.C.E. agents having no interest in pursuing undocumented students on school grounds.

Still, students worry that may change. And there’s no saying what may happen to them outside of school.

“Knowing that at any time, they could just come to my house and take me out of the country was kind of surprising,” senior Christian Lopez said.

On Feb. 7, I.C.E. swarmed a local Mexican restaurant, El Potro, in Liberty, MO.. Clay County Sheriff Will Akin told The Kansas City Star that federal agents were supposed to be investigating a single person’s warrant associated with sex crimes. However, they ended up detaining at least 12 employees and impounding two boxes of employment documents.

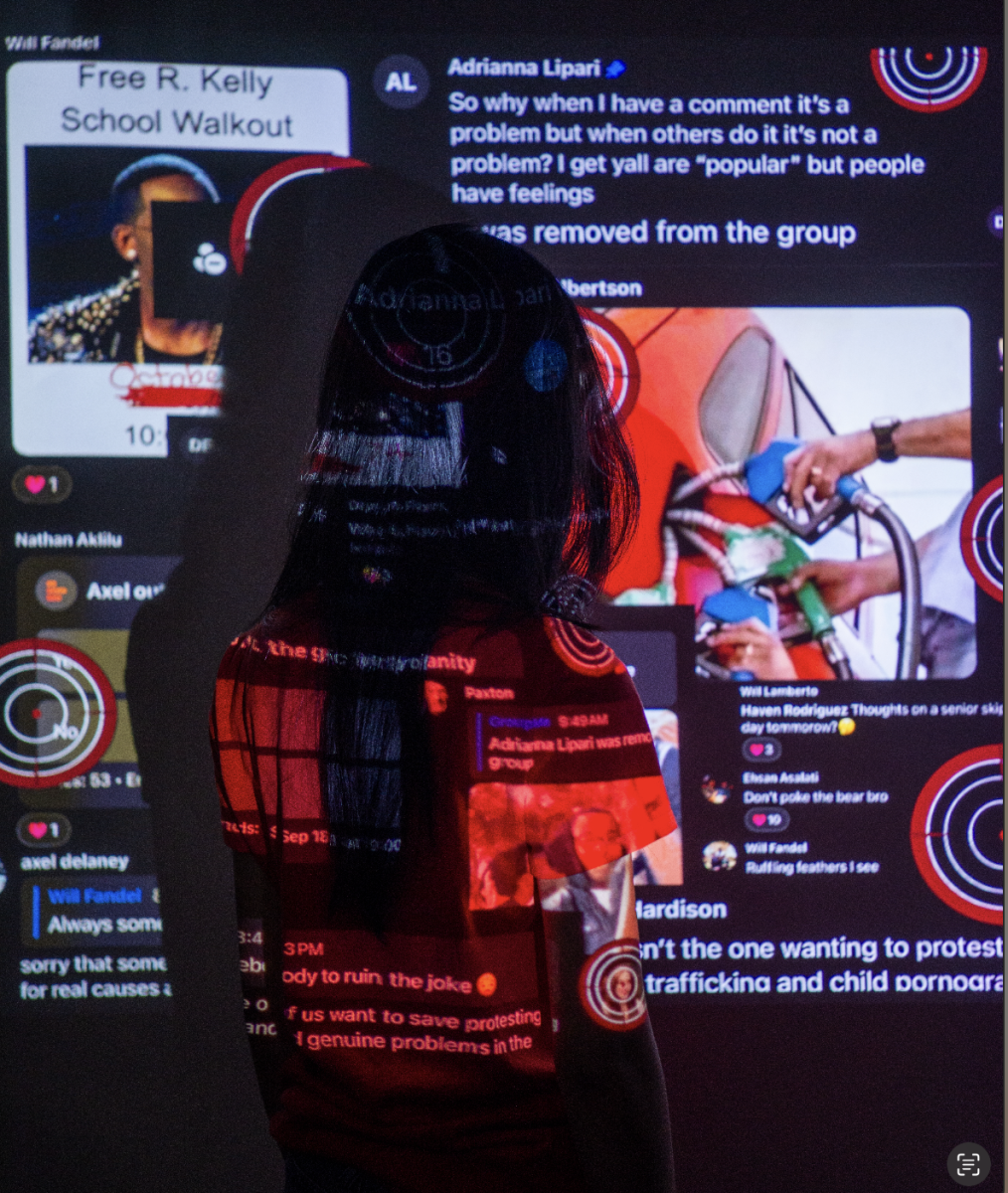

Videos regarding that raid surfaced instantaneously across platforms like X, Youtube, and Facebook. More videos of raids continue to sweep the internet from apartment complexes being infiltrated in Denver, Co., to arrests being made in Northern Virginia.

Now students are scared to drive, let alone leave their homes.

Like senior Pancho Garcia.

Ever since Trump took office, Garcia has not driven to school. The 15 minutes there and back are too risky, he says, so he does his assignments from home. He knows the attendance points aren’t worth being deported to Honduras.

“I can’t go back,” Garcia said. “Everything is a danger out there. People just don’t realize it.”

The hardest part of Garcia’s journey wasn’t walking for miles from Honduras into Guatemala or riding buses, getting stopped, sent back and then having to start over. Or even going through Chiapas, Mexico, and facing violence and corruption from drug cartels and police. It was watching others struggle and knowing there’s nothing he could do but look the other way and keep trying to survive.

Garcia had been deported twice in the span of three years. He’s traveled hundreds of miles to be where he is now. He did jobs for cartel members, moving drugs so they would let him cross the river safely. He avoided joining their gangs, but if he were to go back now, that wouldn’t be an option.

“They will kill me and my family,” Garcia said.

He carries that with him at every sight of blue and red flashing lights and the sound of a siren. That, he thinks, could be all that’s standing in the way of life or death.

Lopez traveled to the United States from Guatemala, his home country, six years ago.

He can still remember sitting in the front yard of his childhood home at 2:00 a.m., stargazing. The warm breeze mixed with crammed luggage and his parent’s arguments were starting to sink in. There would be no saying goodbye to his friends or classmates. No more wandering the familiar streets of Guatemala City in flip flops. No more sipping Coke from straws in twisted plastic bags.

Before leaving, he packed up his 200 car Hot Wheels collection. He had fond memories of racing them up and down his muddy driveway for hours. Now, they’re tucked away somewhere in his Kansas City home.

“I came here and didn’t know how to speak the language,” Lopez said. “It was the first day of sixth grade. I went from being popular to the immigrant kid. When it came to group projects, no one would be with me because I had an accent. It felt like I didn’t belong here.”

Lopez tested out of English Language Learner (ELL) programs in 7th grade. Because he’s not in the ELL class, Lopez says friends tell him he “doesn’t act like an illegal.” ELL students still talk to him about being bullied in school by English speaking students.

“They don’t know what people are saying,” Lopez said. “They just see people pointing and laughing.”

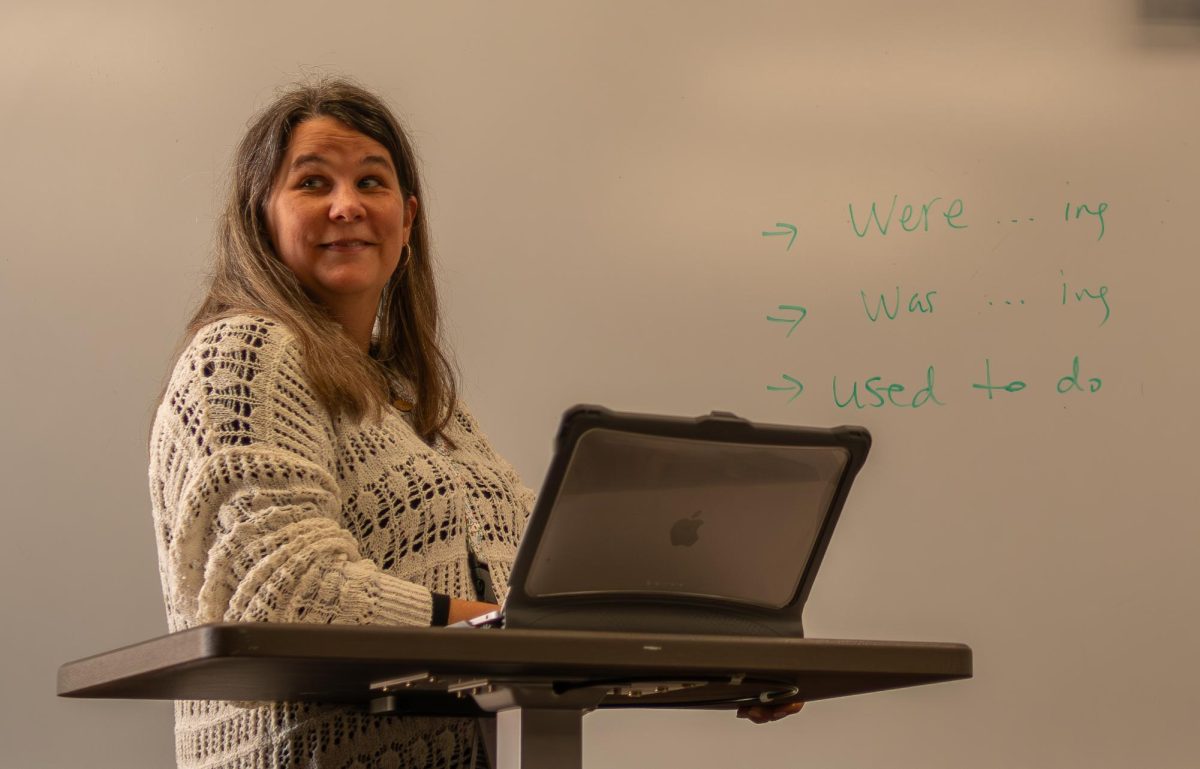

Over the past couple months, ELL teachers Jamie Ledbetter and Nancy Blackburn have had to bring in additional resources that address extreme cases of anxiety, panic and stress in their students – responses which they both say have become apparent now more than ever.

“We’ve had students crying in our office about situations they deal with,” Ledbetter said.

Ledbetter said the ELL department have practiced breathing and relaxation techniques with students and gone over family emergency concerns if, for example, a student goes home to an empty house because family members have been detained by I.C.E. agents.

“Our students are children, they are not adults, these are children,” Blackburn said. “So they are put in this situation without a lot of choice. But we are trying our best as their teachers to make sure our students feel that they have some control.”

Ledbetter said finding resources to alleviate specific burdens their students face is part of their job. This could even mean legal advice.

“The thing that people don’t realize is, I’d say the majority of our students are working with an attorney,” Blackburn said. “They are trying to do the right things and become a legal citizen.”

Teachers also spend time supplying students with academic help, local experts and organizations that provide necessities like clothing, toiletries and more — or just being a person who can sit in that office chair, look them in the eyes and simply listen.

“The most important thing is that at Shawnee Mission Northwest, they walk through those doors and feel like they belong here,” Blackburn said.

Ledbetter pointed out how their students are resilient, but that doesn’t stop her from envisioning worst case scenarios.

“It is scary to think that there is a student we may never see again,” Ledbetter said.

Every day, that thought will become a student’s reality.

“Just because I open a f***ing door,” Lopez said.

Contributors: José Duran and Emma Wyckoff