Last year, sophomore Colin Cummings stood in line for the water fountain. It was the final week of summer football conditioning, and the players had tubs of pre-workout in their hands. They were “dry scooping,” pouring cupfulls of the chalky white powder into their mouths before taking a sip of water and trying to swallow.

Last year, sophomore Colin Cummings stood in line for the water fountain. It was the final week of summer football conditioning, and the players had tubs of pre-workout in their hands. They were “dry scooping,” pouring cupfulls of the chalky white powder into their mouths before taking a sip of water and trying to swallow.

Cummings was doing the same.

“I took, like, four scoops,” Cummings said. “A gram and a half of caffeine.”

Pre-workout is a powder supplement that’s mixed with water to give athletes and gym bros an energy boost that improves focus and endurance before they exercise. Their main ingredient is caffeine — one scoop is equivalent to downing three cups of coffee, according to the Nebraska sports medicine program.

High doses like this can be harmful to teenagers’ health.

According to the Columbia University Irving Medical Center, kids and teens should consume no more than 100 mg of caffeine daily.

But, in that day alone, Cummings took 1,500-times this amount.

“I threw up from that,” Cummings said. “It was rough.”

At Shawnee Mission Northwest, 72% of teenagers that responded to a poll say that caffeine is part of their daily routine, and 55% have more than the recommended amount. It dominates many aspects of teen’s lives — from the iced caramel macchiato first thing in the morning to the scoops of pre-workout before sports.

Caffeine has been around for centuries, but 17 and 18-year-olds are now consuming nearly double the caffeine they were a decade earlier, according to NPR news. Too much can lead to negative side effects like heart palpitations, high blood pressure, anxiety, sleep problems and more. Even the popular energy drink brand Celsius admits on their website FAQ page that their drinks aren’t recommended for children under 18.

In extreme cases, caffeine can be dangerous. Infamously, Panera discontinued its Charged Lemonade in 2024 — which could contain up to 390 mg of caffeine — after two wrongful death lawsuits, one a 21-year-old female college student and the other a 46-year-old man.

But vomiting back up a gram and a half of pre-workout didn’t stop Cummings from using the caffeine-filled supplement again, nor will it stop others.

Junior Sam Ousley first started drinking caffeine in hopes of helping his ADHD, since studies have found that it dulls the symptoms and boosts concentration. He used to bring four cans of Pr Pepper to school to get him through the day, but–

“There was more than one instance in which all four would be chugged by the end of second hour,” Ousley said.

Now he wakes up craving caffeine, with pounding headaches as soon as he opens his eyes — a common symptom of withdrawal.

“I would not survive if I did not drink coffee in the morning,” Ousley said flatly.

Now he’s trying to cut caffeine out of his school day, keeping his coffee and soda at home. Still, he estimates that he consumes 80 to 200 mg regularly.

Ousley acknowledges that he has “an addiction.” He’s tried to quit several times, but his resolve has never lasted.

“I decided it wasn’t worth it,” Ousley said. “I mean, the benefits to caffeine are pretty clear. You’re more awake, more hyper, more active. In my case, much more focused.”

Energy drinks are the most po1pular way students at Northwest consume caffeine according to an Instagram poll, followed closely by coffee.

The National Library of Medicine says that energy drinks are often targeting teenagers through strategic advertising campaigns. Social media algorithms push ads tailored to teens, and influencers on platforms like Instagram and TikTok can be seen endorsing energy drinks as popular ways to get a boost. Even celebrities Logan Paul and KSI have created their own energy drink brand, Prime Energy.

Junior Louisa Bartlett loves Starbucks lattes and Alani energy drinks. She first started buying them in middle school after seeing her friends at dance carrying around cans of Celcius.

“Like, everybody had them,” Bartlett said. “So I was like, ‘Oh, might as well.’ And I haven’t gone back since.”

Bartlett has tried to lessen her caffeine intake recently by going on an energy drink cleanse. It lasted for a few months, but she popped open a new can a few days ago.

“It was kind of disappointing,” she said. “Here we go again. We’re back on the grind.”

Access is rarely an issue with caffeine. Students will always be able to find a cup of coffee at the Starbucks drive through, energy drinks at gas stations and caffeine additives at the grocery store. Even at Northwest, students can grab a caffeinated drink from the vending machines.

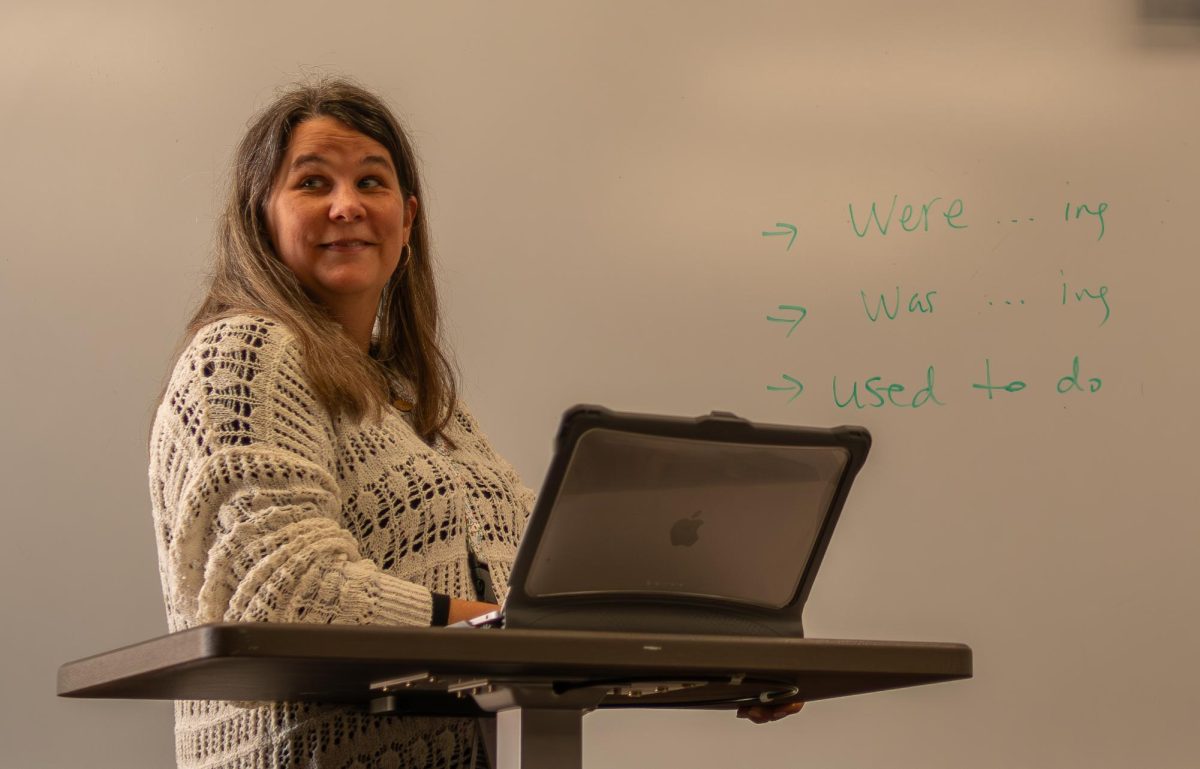

School nurse Wendy Woods says that she sees students in her office for caffeine-related jitteriness about once a month.

Woods herself has seen a nursing student have his heart restarted after a caffeine overdose, and warns students with this story.

But, she does say there are safe ways for teenagers to consume caffeine.

“A good, old, plain cup of coffee — maybe some cream, try not to have a lot of sugar in it — or tea is nice,” Woods said.

She recommends drinking caffeine thirty minutes to an hour and a half after waking up naturally to prevent dependency.

Even with all its flaws, caffeine isn’t going anywhere, especially for teens.

In the end, students will keep reaching for the colorful cans full of caffeine.