The bus ride to Shawnee Mission North Stadium is nearly silent.

On Oct. 4, the varsity football team, dressed in black, barely says a word. With hoods up, and headphones on, they listen to music, stare ahead and scroll on their phones. In less than two hours, they will play Olathe East High School at Northwest’s homecoming game.

On the field, players stretch in a circle and practice tossing footballs back and forth. Senior Logan Morley listens to jazz as he walks up and down the sideline. Eyes closed, he envisions himself, the quarterback, throwing a perfect pass. He clears his mind.

He tries not to think about Ovet Gomez Regalado, his teammate who passed away nearly two months before on August 16. Ever since Ovet’s medical emergency during football conditioning, the team has been forced to deal with the fragility of life. They want to make every turnover, touchdown and field goal for Ovet.

“A lot of peoples’ eyes have opened from it,” senior and fullback Ray Gomez Regalado – Ovet’s older brother – said. “We have to play as hard as we can because you never know when your last game is gonna be.”

Ovet was a sophomore — he played on the freshman team last year, but likely had a junior varsity season ahead of him. The football team is finding ways to move forward because living in the past is not an option. They still want to win games and make it to state, but that doesn’t mean forgetting Ovet.

In the days following his passing, coaches wanted to give players a break. But the team showed up to practice anyway.

“We use practice as a way to grieve,” senior and defensive lineman John Harris-Webster said.

“In a way, it’s become my therapy,” Ray said.

After every practice or workout, the team prays for Ray’s family and their health.

There was no formal discussion, but instantly, players say everybody showed up with a new determination. They ran drills, took ice baths, stretched, lifted weights and drew up plays. They were able to work through their emotions out on the field. It became a second home.

“Ovet wanted to get better for us,” Harris-Webster said. “Seniors knew what a season demands of the team. I don’t think compromising our ability to play by taking off football would have been what he wanted.”

So they kept practicing.

Football is a hard contact sport: players slam into one another. Parents yell at referees, referees yell at coaches, coaches yell at players. It’s what Harris-Webster likes to call “tough love.” It isn’t for the weak of heart. Yet to them, it’s an outlet.

They play to get their frustration out. They play to see themselves grow. They play to feel something.

Football isn’t just a sport.

“In no moment does football leave my mind,” Harris-Webster said. “We go to school to play football. We push through, 7:40 a.m. to 2:40 p.m., to play football.”

Football is a way of life. It’s how the team processes one of the hardest things they’ve ever been through.

Two wins, two losses, no ties. That’s what their season amounted to before the homecoming game.

Players shake off nerves. They crowd beneath the giant inflatable cougar, its paws creating an arch for them to race through.

The clock strikes seven.

* * *

Over a year ago, Ray was excited to see his little brother, Ovet, rooting from the sidelines at varsity games.

Now, even with hundreds of people watching, chanting and screaming, the stadium feels empty without him.

“When I first started going to school or practice, it was mentally draining,” Ray said. “It’s still hard. But I know everyone out there cares about me so I’m more comfortable playing.”

Not only that: Ovet’s loss helped the team create stronger bonds.

“Obviously we could delegate wins to him, but more so we live our lives like Ovet,” sophomore and defensive end Noah Lee said.

It inspired Harris-Webster to become a role model for younger athletes. Whether that’s through playing video games together, cracking jokes in the locker room, giving advice and encouragement or watching college games at Johnny’s Tavern on weekends.

“We all became family,” Harris-Webster said.

After practices, teammates and coaches pulled Ray aside, and ask how he was and what they could do to help.

“They were always my brothers,” Ray said. “But it just became so real seeing everyone rally around me.”

Coach Bo Black still calls and texts him to check in almost every day.

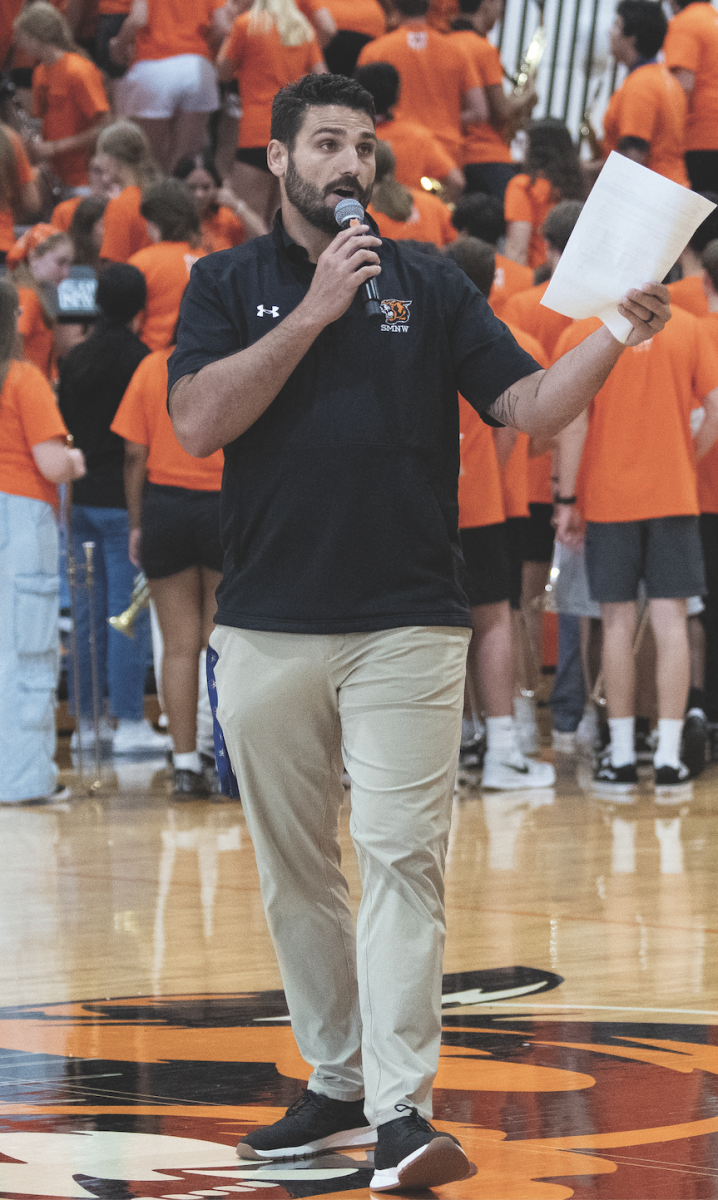

“In my opinion, it’s about giving to others,” Black said. “There hasn’t been a day we haven’t mentioned in reminding each other that football is bigger than we are, and life is bigger than we are.”

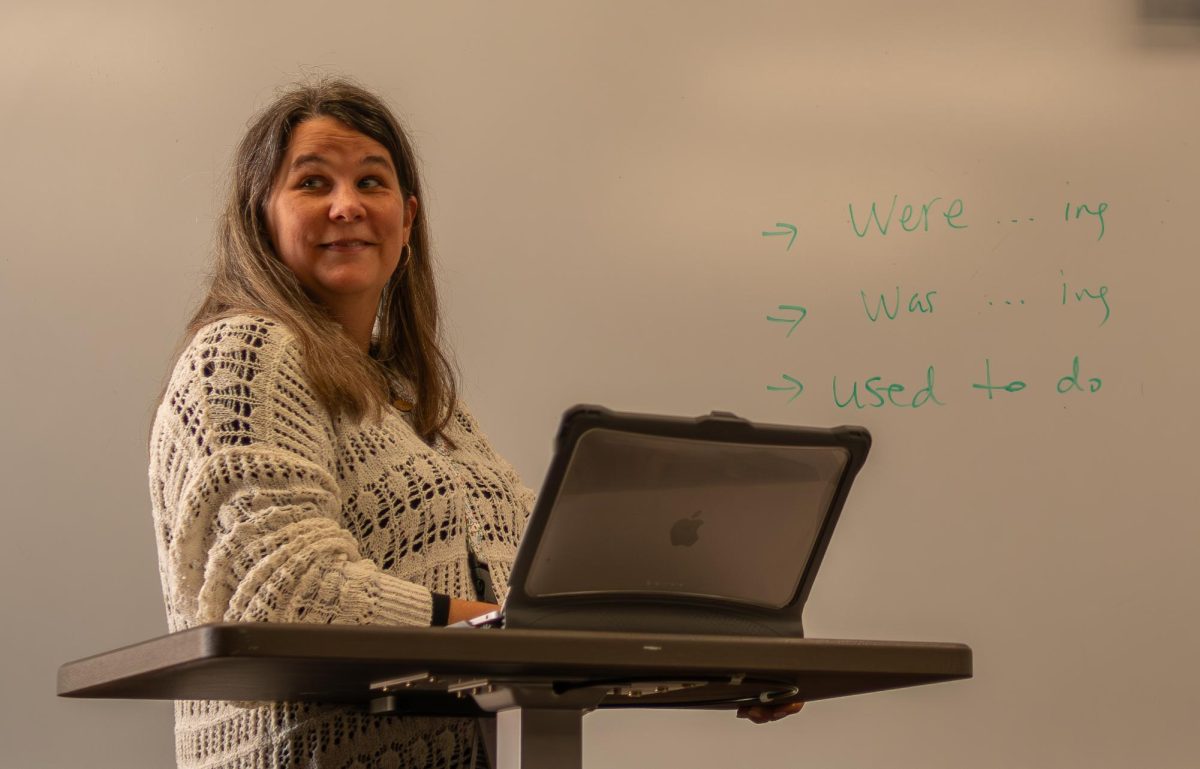

Black runs the field. He’s been coaching for 29 years, and has been at Northwest for 10 of them.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” Black said.

Ray’s presence alone was enough to motivate the team. If he could leave that hospital and still show up to class on time, then so would everyone else. If he could go to his brother’s funeral and still give 100% at practice, then so would everyone else.

“That he showed up to workouts has really encouraging the rest of us,” senior and linebacker Owen Barth said.

Their most recent game was against Shawnee Mission West, beating them by 50 points.

So the pressure was on.

The homecoming game is a back and forth battle. Northwest scores first. Teammates smack one another’s helmets and shoulder pads as they come off the field. On the sidelines in between plays, they cluster around a TV screen to rewatch their mistakes. Drenched in sweat, they drink from Gatorade bottles, spit and wipe their faces.

It’s tied up, 14-14.

The stands are crowded: a sea of red, white and blue. Students wear glittery cowboy hats, tutus and drape American flags over their shoulders. Screams and cheers ring out.

A day earlier, the team saw a much different scene. It was Oct. 3.

Ovet’s birthday.

Ray and some teammates went to visit his grave site. They all sat, talked and ate food. Reminiscing felt good.

“That’s all we can do,” senior and defensive end Harper Engel said. “Is be there for .”

The stadium lights blot out stars. Even with the score at 28-14 in Northwest’s favor, they don’t get comfortable. Coaches shout at players.

“We’re making f***ing excuses!”

“Are you satisfied?”

“This is not over! We’re still at war.”

Olathe East scores a touchdown and makes their extra point.

It’s 31-21 with three minutes left on the clock. But the Cougar’s defense holds.

As time runs out, players rush out onto the field to jump onto one another and give celebratory handshakes.

Shawnee Mission Northwest wins, 31-21.

And now, the bus ride back home is anything but quiet.

Players dance in the back rows, blasting rap music. The wind whistles through the open windows. They shout and laugh and sing.

There’s no question as to why any one of the players on that team was at the game. There’s no question as to why they kept showing up to practices as opposed to pausing the season. There’s no question as to why they run drills and watch film for hours. It isn’t because they’ve forgotten about Ovet, but instead found a way to grow stronger and keep pushing themselves to be the best they can.

“Now we play with purpose,” Ray said. “I play for my brother.”