Spring. Fourteen years old.

It’s a regular afternoon for me — homeschooling for less than an hour, doctor and therapy appointments, rotting on my bed listening to Radiohead — and hiding almost everything from my mom. I’m 14 and sneaking out at night, getting blackout drunk, and sneaking social media — all after recovering from an eating disorder. Mom has no idea.

When I walk upstairs to the kitchen, my mom is looking at me.

“Pack your things,” she says. ”You’re going to Emaw and Papa’s house.”

She found out. I trusted my little sister, but she was 12 and tattled.

My mom drags me into her black SUV. She can’t handle me anymore. She has to focus on her other 3 kids, in hopes that her parents can take care of me.

Humiliating.

We listen to 99.7 FM in silence on our way. We arrive at the retirement home 30 minutes from our house. My grandparents are playing “The Chosen” on their living room TV, a Christian series.

I’m not allowed to be alone, so I sleep on their stiff, pillowless couch in the living room with a thin blanket.

Every day is a blur to me, I can hardly remember the details. The fourth day passed.

And I tell my grandma — I want to end my life.

Again.

****

Spring. Seven years old.

I stand outside the Oaklawn Montessori School basement when I hear IT.

The “make my heart drop” IT.

“Hey Sage, wanna help me with the speakers downstairs?” IT says to me.

IT, The Principal, Denis Creason.

God, I hate that name.

Help with the speakers… I know what that means.

Six buildings, and the one IT leads all the elementary school girls to is a logged cabin, with a music basement, where we would “help with the speakers.”

The basement trips happened up until the end of 3rd grade — when another girl told her mom. And her mom told all the other moms — about the wrong IT did to US.

I never went back to Oaklawn.

****

Fall. Eight years old.

I wear a black and red floral dress, rainbow glasses, and a short bob

I walk into the courtroom and see IT. His greasy, gray, long, curly hair, and his grayish black musty mustache.

They didn’t tell me he’d be here.

My chest, my heart, all sink.

Standing next to the judge, they show me a picture of the building

“What building is it called?” IT’s lawyer said.

“Um um um.”

My lawyer told me not to say um, but I was 8 and I did.

“Wooden building.”

“Incorrect. It’s the logged cabin,” IT’s lawyer said.

Walking out of the courtroom, I see my mom and dad with a proud look on their face. Afterward, my grandparents, my parents, my siblings and I go to Applebee’s. I eat a hamburger with ketchup only.

A few years later, he was found not guilty.

***

Spring. Thirteen years old.

We’re about to go on stage when I tell my friends — “I feel dizzy.”

Shoot. Here we go. The blurry lights, the small church crowd cheering, another ballet performance, except this time, my body is running out of energy.

My life is full-time ballet and homeschool, and when I’m not doing that I’m going to high school parties and drinking orange juice mixed with vodka. I’m on my second week of only eating lettuce and ice, sometimes carrots. I have no energy to do anything — let alone dance.

My gut doesn’t feel right about this.

Clack-clack-tap-clack-tap.

We begin. My slick back bun and the bobby pins hurt my scalp. Ouch.

The lights are getting fuzzier. Am I okay?

As I run off stage, my sight begins to fade.

“I don’t feel too good,” I tell my choreographer.

I pass out in her arms.

****

A few weeks later, my girlfriend, the first girl I was serious with, the first girl I kissed, the first girl who knows me, texts me at midnight, “We’re over.”

Shit shit shit. Can I go on without her?

Can I?

I decide I can’t.

I grab my gray bed sheets and toss them over the bare, unfinished basement beam. I’m going to tie it around my neck. I grab a chair and stand on it.

I stop myself.

I walk upstairs and cry to my mom.

“Mom, I want to end my life.”

“Oh my God,” she says. “Get in the car.”

****

Mirallac. A mental hospital for suicidal kids.

Wow.

Fitting? I guess? I don’t know.

Me and my mom, at midnight, walk into this freezing building and I give them all my stuff: My jewelry, my phone, my makeup, my socks and shoes.

I take an hour-long survey.

“You typically stay in here for three to seven days.” The lady keeps speaking gibberish.

Eventually, I had to give them my clothes so I can wear the gray sweats with a blue tee-shirt assigned to me.

I had to talk to a psychiatrist while there.

“We believe you have Anorexia.”

4 days later, I arrive home. Nothing changes.

****

Spring. Fourteen years old.

At the retirement home, after I tell my grandma, we call my mom. My dad picks me up around dinner time and takes me back to Mirallac. It’s cloudy and dark out. On our way, we listen to Weezer.

I get accepted — for the third time.

My first six days, all I remember are the dry eggs with too much pepper every morning.

On the seventh day, they suggest long-term help. My mom and therapist agree.

I don’t hesitate.

This isn’t who I want to be known for. Who I want to be. I’ve lost friends, my phone, my room and now, my family. This’ll be rough, but this is what I want to do. What I need to do. I need to get better.

Off I go, another mental hospital.

Except this time, for months, 10 hours away from my home, my mom.

****

Summer. Fourteen years old.

Riiiinggg riiinggg

My mom’s here, oh my gosh, my mom’s here.

It’s been two months since I’ve seen her. I feel more relieved than excited. To hug someone, my mom especially.

Instead of flying out to pick me up, she drove.

I’m standing in the exit I haven’t seen since I walked in. I’m holding a pink soft, weighted bunny stuffed animal my friend gave me before I was admitted – a reminder that just like I walked in with the bunny, I’ll walk out with it. My mom helps me carry my suitcase and we head to her car, the same car I got dragged into. I can smell the lavender lotion she still has in her car. “Can I play music?” I asked. I made a 10-hour playlist for the car ride home, mainly filled with TV girl, The Smiths, and some Nirvana.

In Colorado, I learned how to manage my anxiety. I never thought I’d be comfortable with being alone, no close friends, no relationship—just thriving independently. Of course, I had people to talk to, but in Colorado, I found safety in myself. And not once had I felt that until then. I did experience the worst known to man cheese sticks. They were soggy and they didn’t peel. Awful.

I don’t know who I want to be yet, but I know who I don’t want to be, and that’s a start. I will never be who I was again; I’m not ashamed to say that.

We pull into the driveway and I turn off the music.

My mom turns to me.

“I see light in your eyes,” she says. “And I haven’t seen that in a while.”

I smile. I needed to hear that, especially from her.

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal ideations, you can call the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. The Lifeline provides free and confidential emotional support to people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, across the United States.

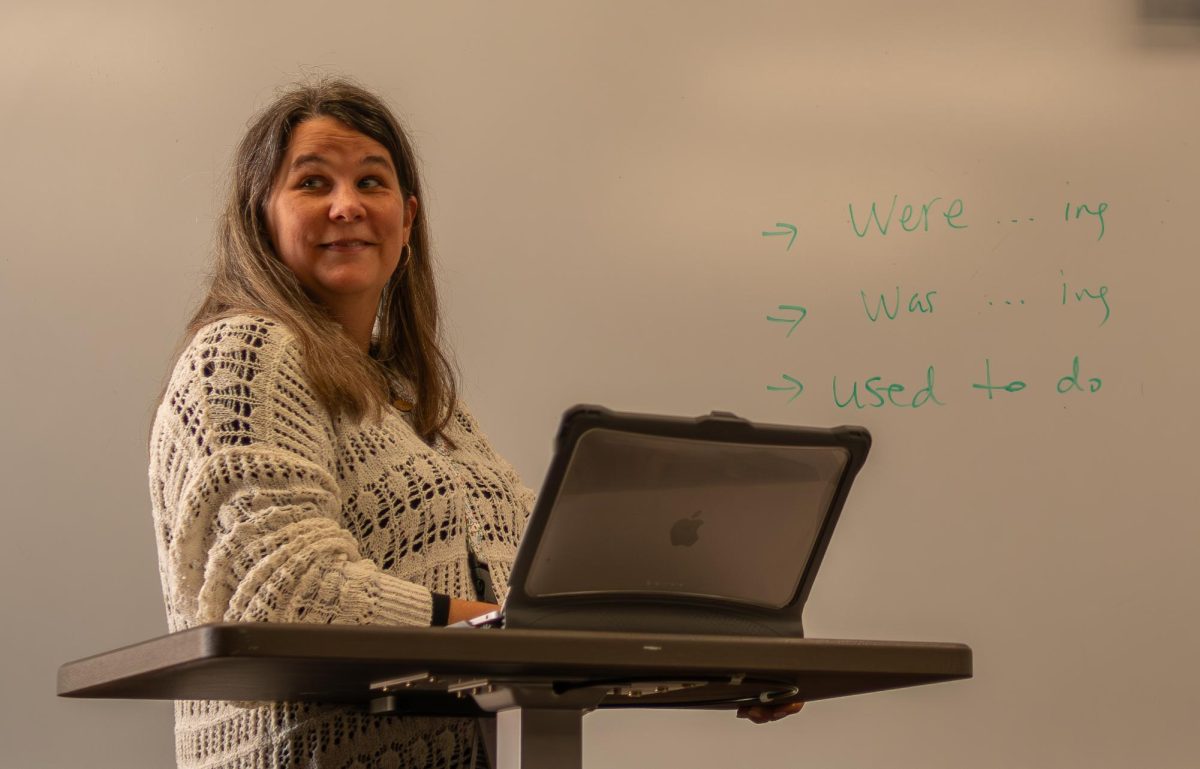

You can also contact school social workers Tina Clark (brclark@smsd.org) and Melissa Osborn (nwosborn@smsd.org) at the front office.