Sophomore Jillian Thimesch’s alarm blares on her bedside table.

She hits snooze once, then again and again until she realizes it’s an hour to noon and school started at 7:40 a.m.

But at this point, why bother?

Instead of grabbing her car keys, frantically combing her hair and racing out the door, she decides to just stay home. This may annoy Thimesch’s parents, but not enough to drag her by the feet. This may make Thimesch feel guilty, but not enough to leave her bed.

In total, Thimesch has more than 20 unexcused absences this school year, meaning she’s considered chronically absent.

“It doesn’t take long for us to finish that one little work sheet in math,” Thimisch said. “I feel like I’m just scrolling through social media for the rest of the day, when I could get it done at home and take a nap.”

Thimesch isn’t alone: she’s part of a national trend of high school students who are choosing not to come to school.

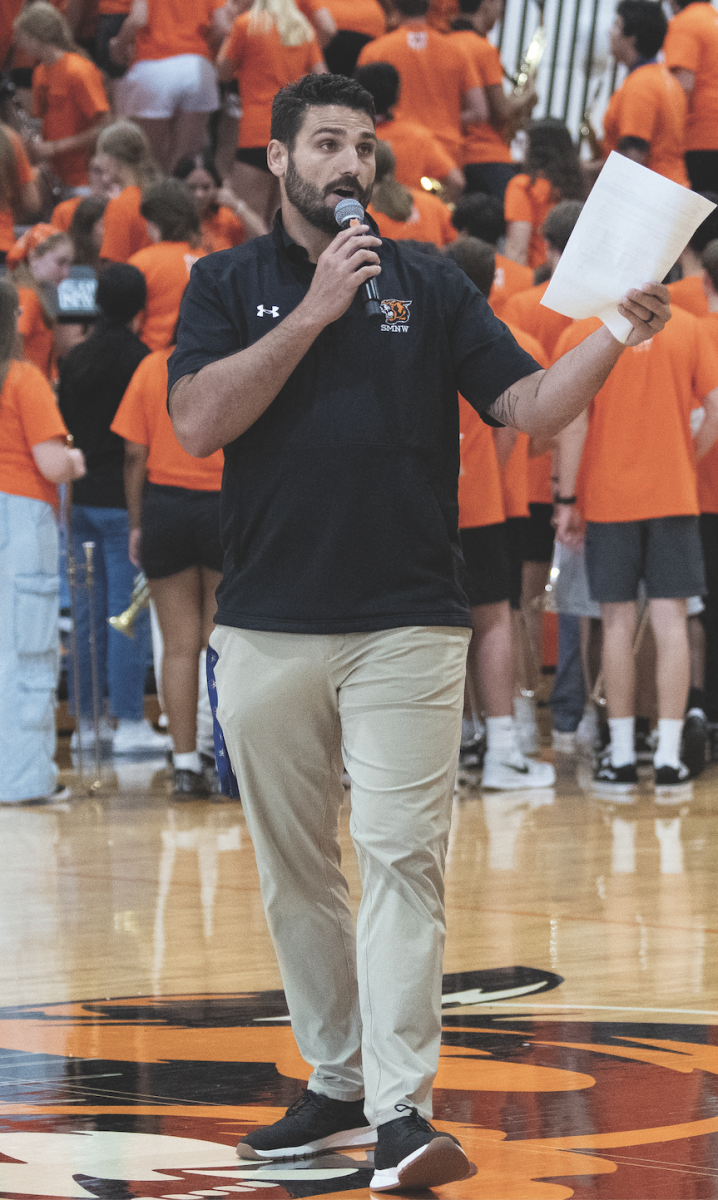

“There’s not a district who isn’t experiencing this,” Northwest Attendance Specialist Tyrone Foster said.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, a student is considered chronically absent once he or she has missed at least 10% of school days or 18 days in a year for any reason, excused or unexcused. This is different from truancy, which only categorizes excused absences. In total, 21% of Northwest students are presently chronically absent, nearly twice as many as a decade ago, according to data provided by the Northwest Office.

For the senior class at Northwest, 35% are chronically absent, whereas for freshmen it’s 13.8%. According to incoming Superintendent Dr. Michael Schumacher, 20% of all high school students in SMSD are chronically absent, as are 44% of all seniors.

“We need our students in our building so that we can provide them all of the support that they deserve,” incoming Superintendent Dr. Michael Schumacher. “Lower performance, and mental health concerns are incredibly troubling for us.”

Around Northwest, group essays are submitted unfinished, lab observations incomplete and seating charts sparse, causing tensions to rise between students and teachers as the district continues to search for answers.

“If it were an easy problem to address then there wouldn’t be a crisis,” Chief of Student Services Dr. Christy Ziegler said. “That’s why it’s important. “There’s all kinds of data regarding student success later in life. But if you’re missing your education that impacts your job, your future and so forth.”

COVID-19 has had a major impact on school attendance, according to Ziegler. Not only are students more prone to stay home for every sniffle and sore throat due to previous regulations, but aspects of online learning have given many a sense of normalcy.

If a high school student has the chance to complete their assignments or take notes through Canvas, they fail to see the benefits of in-person learning.

“That really tells us that we need to make sure they’ve got a reason to come to school,” Ziegler said. “That there’s engaging instructions, and students can feel they belong.”

Despite state laws requiring that students meet a certain level of attendance, they may miss school for a variety of reasons, according to a handout from the Kansas Department of Education. Many are absent due to barriers such as chronic illness, house instability or poor transportation. Others struggle academically, socially or are bullied. Some students feel disengaged, with no meaningful relationships established with adults in school, discouraged due to lack of credits or are lacking culturally relevant material/lessons.

Some students fail to see the reality or consequences of their actions when skipping — which can lead to involvement with the district attorney’s office, possibly sending their parents or guardians to court. Instead, they brush off the warnings and letters sent home as empty threats.

“I haven’t been to math in two months,” senior Brooklyn Bridwell-Keaton said. “I’ve just accepted the failure there because I was gone so much, I use second hour as a free period.”

Some teachers take severe offense to students who skip, others find ways to adapt their teaching styles, such as posting video notes or updated modules and many have accepted what’s out of their hands.

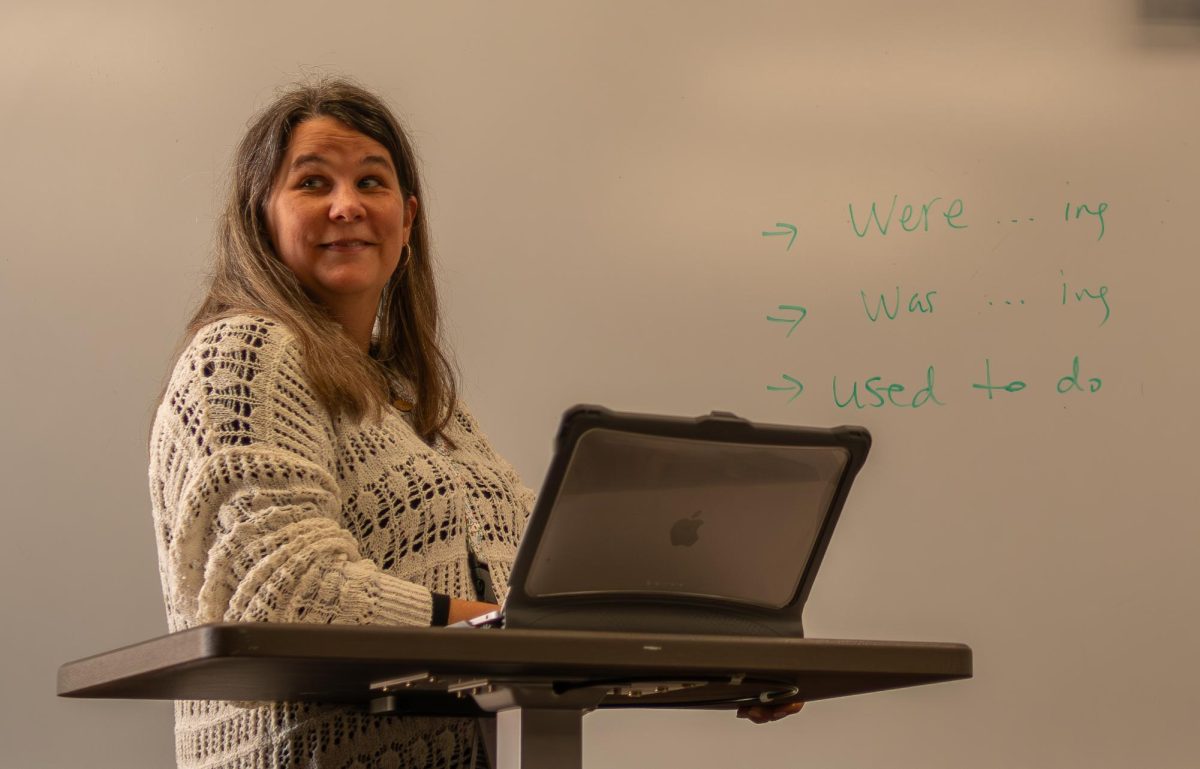

“I’ve been teaching for 17 years,” English and creative writing teacher Sheila Young said. “And absences are the worst I’ve ever seen. I don’t take it personally, but I do worry about it.”

Math teacher Mira Davidovic says as attendance has dropped since COVID, she feels annoyed and sad because she cares about her students.

“People who end up with a D move on and continue to struggle in other math classes,” Davidovic said. “There’s just nothing I can do about it.”

Science teacher Michael agrees.

“It’s their education,” Pisani said. “If it were my kid, I’d be walking them to class. I don’t wanna say too much more and get myself in trouble.”

IB Diploma students, track athletes, cheerleaders and theater kids alike are beginning to experience burnout or something similar. Even though less is expected of them post COVID. Logic might justify that there are only a few more weeks left, a couple tests, and some half days, but that doesn’t stop them from hitting the snooze button like Thimisch or pulling into a Starbucks drive through instead of the student parking lot.

“It’s complicated,” Thimisch said. “If I really wanna go home or I’m desperate I’ll sometimes fake an illness. But usually I just won’t show up in the first place. It’s nice to have a rest day every once in a while, but missing class has definitely dropped my grade. So the guilt is there.”

Some students also tend to suffer from mental health issues keeping them from school.

According to Bridwell-Keaton, the average classroom setting doesn’t meet the needs of students prone to hyperactivity. She proposed lengthening passing periods and letting all students listen to music during work time in order to keep more of them in class.

“I have chronic ADHD,” Bridwell-Keaton said. “I have to have four different modes of brain stimulation to be comfortable. I’m in the back room in Yearbook, playing a game on my phone, while designing and there’s a Youtube video on. And I get my work done.”

Some parents, such as Thimisches’, have offered to buy her a PS5 if she can make it a full month in school, whereas others have given up entirely.

District officials have worked tirelessly brainstorming ways to keep students in class. Is the answer social media, sending email blasts to parents, PJ day?

According to Ziegler, SMSD will utilize Sources of Strength to promote inclusivity, and address any feelings of anxiety.

Attendance specialists, such as Foster, have also been hired recently, across the district to monitor rates of chronic absenteeism in high/middle schools and to increase communication with student families.

“The way I present it to them, is a goal,” Foster said. “It’s a small goal, but an important one. ‘Just two more weeks,’ I say. I’m not gonna get everybody because not everybody’s gonna buy into that. Some kids are like, ‘I don’t care.’ Some parents are like, ‘I’ve had it up to here with them, I don’t know what to do.’”

On his desk, Foster has a list of between 30-40 student names that are on the path not to graduate. He claims that if he can get at least 80% of those students to walk the stage come May, then he’s done his job.

Until then, teachers will continue to unload their frustrations, students will sleep through first hour and administration will ask the same questions.

“I’m trying to improve,” Thimisch said. “I swear.”