Eyes darted to Amber Underwood. Students watched as her silver zebra striped skirt swished, and hot pink acrylics zipped up and down the body of her flute. This was the first time since 1997 that Underwood had stepped foot on the waxed floors of the Northwest gymnasium.

Music, specifically flute playing, started as a hobby, which led to performing at a few local venues and restaurants. Then there were gigs in New York, Atlanta, Mexico and Chile. Now, Underwood is starting her second album, and hopes in the next three years to be nominated for a Grammy.

She grew up in Wyandotte, Kansas, and began learning the basics of piano in third grade.

Now fans from afar pay to watch her perform in glitzy heels.

Underwood graduated from Northwest with the class of 97’. She was crowned homecoming queen, was involved in orchestra, music theory, swimming and many clubs.

Underwood knew that to not pursue music would be wrong, but to ignore her other passions, especially those that guaranteed a steady lifestyle, would be wrong, too.

“I always saw myself as some type of performer,” Underwood said. “I wanted to be someone on stage, I knew I had it in me.”

She attended Wichita State University on a full performance scholarship, then went to Oklahoma State University to observe a professional flautist.

Underwood eventually joined a startup program at the UMKC Conservatory for a music business and arts administration degree.

“I studied under Bobby Watson, a world renowned saxophone player,” Underwood said. “He really jumped me on the jazz scene in Kansas City. I like to say I’m a street jazzer, that I don’t have a degree in jazz, I learned it from the streets, from elder statesmen. They passed down knowledge of jazz, transcribing records and going to jam sessions. I was the only female going into these places, so they automatically assumed I was the singer. It was like a badge of honor being able to play with them.”

Underwood is trying to change the way people see jazz. Growing up, Black female composers, let alone female composers, were obsolete, if not overshadowed by men.

“When you look past the singer, it’s a lot of guys,” Underwood said. “And I want to be the next Prince, or female version of Micheal Jackson. I haven’t seen a flute player rock it out before like Lizzo. And I’ve been doing what Lizzo’s been doing long before she’s been doing it.”

She decided to pursue both passions of advocating for female instrumentalists on the jazz scene and encouraging new forms of expression with younger generations.

Flutie Nastiness, her band, was established in 2008.

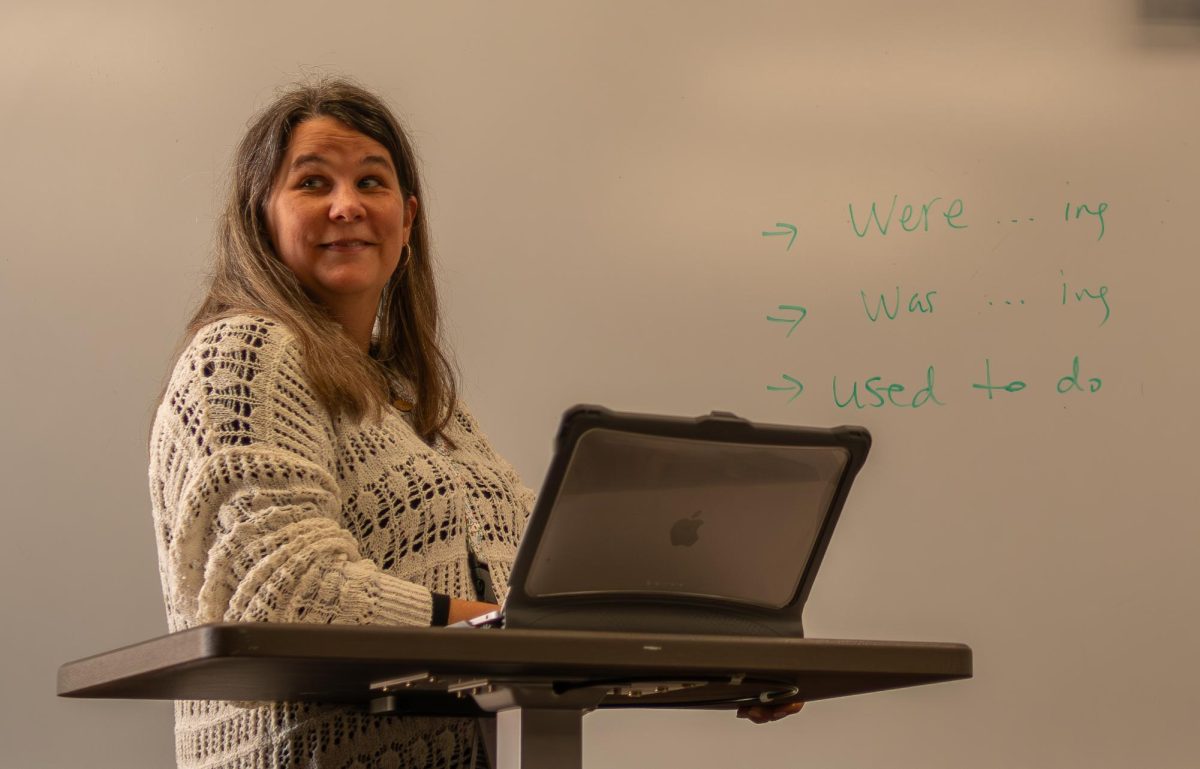

Since then, Underwood has juggled teaching by day in fluorescent lit classrooms at Central and Northeast middle school, and performing by night in ambient jazz clubs.

A few weeks ago, Underwood was asked to play at the Northwest Black History Month assembly.

There was no hesitation.

Seeing the diverse student body, separated by bleachers, cheering, and showing appreciation for her work, her music, made Underwood swell with pride.

Underwood’s former jazz band teacher Doug Talley was also there to witness Underwood’s performance; he hadn’t heard her play since junior high.

“She transferred in during middle school,” music teacher Doug Talley said. “At that time she was actually quite a bit behind. You could tell that she liked to play, but hadn’t gotten very far. She stuck with it. In high school she really excelled and was especially good at state .”

Over the years Underwood has gained a better sense of self. Whether that be wearing bright sundresses to get the mail at the risk of attracting stares, cutting ties to toxic relationships and sharing the spotlight before a crowd of strangers who know her stage name and nothing else.

“Just be true to your art and your music,” Underwood said. “You always want to educate the people that are coming up, Jazz is a Black American music. If you are a non African American and cannot acknowledge it, you cannot embrace what jazz has to give.”