October 28, 2022.

Courtney Allison woke up at 6:00 a.m., which was oddly early considering that for the first time in ages she had time to make breakfast. A Pinterest worthy piece of toast, lathered with peanut butter and honey. She had time to pin her hair just the way she liked it, and time to do her makeup, all without bothering to glance at the clock. Until she made the mistake of realizing an hour already passed.

They were supposed to leave in two minutes and the upstairs usually bustling with the commotion of zippers, bookbags and electric toothbrushes was silent. Allison anxiously texted her 14-year-old brother Tyler.

You up?

You up?

You up?

She rapped on his door, urged him out of bed and groaned as she heard the shower running minutes later.

She pulled in the student lot at precisely 7:39 a.m..

Allison had a doctor’s appointment, she was supposed to leave 10 minutes early at the end of the day. But to her surprise, she was handed a slip with the time to leave circled now, signed by the secretary.

Confused, she called her mom, who sounded off and was coming to get her now.

Her first thought was that somebody died, which was ruled out because otherwise Tyler would be there too. Stepping into her mom’s red RAV 4, the first words she heard was “you’re being admitted”. Did she mean the mental hospital? Allison was painfully confused as to what was happening.

She was confused when she stepped into the ER.

She was confused when she needed a chest X-ray.

She was confused when the doctors said she couldn’t eat.

She was confused when her mom explained that had cancer.

Soon after something inside her snapped, and Allison was forced to pick up the pieces in a hospital gown, drowning in care bears, casseroles and cards sent by teachers, grandparents and kids she hadn’t talked to since the 4th grade.

That day after the E.R. appointment her mother, Andrea Allison, couldn’t face her without tearing up as she clutched the same snotty Kleenex. Slowly she got better at putting on a brave face, at making the “I’m fine’s” more realistic.

It took a while for her siblings to visit. And even then Tyler would look anywhere in the room but Allison. Piper, her 12-year-old sister, gave her a letter about how she felt was losing her sister to cancer. And Jake, the youngest, couldn’t keep himself from making bald jokes. His favorite was about the beige beanie she often wore, asking “where’s your shell peanut?” anytime she’d take it off.

“The hardest part was when you’re hurting like that you wanna blame somebody,” Allison said. “My body was trying its best and I had to come to peace with the fact that I could be dying and I didn’t need to think about it anymore.”

Allison had Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, type B. That is when Lymph Node Cells start to multiply in an abnormal way and begin to collect in certain lymph nodes. The affected lymphocytes, by causing them to lose their infection-fighting properties, make you more vulnerable to infection.

The doctors found four masses (infected lymph nodes) in Allison’s chest and upon diagnosis rushed her into surgery.

“I do remember that I was starving,” Allison said. “All I had was and they needed me to fast for the labs. I had to ask if I could eat and they said no, because I had a biopsy later. I was so thankful for the toast.”

The only symptoms Allison presented prior to treatment was back pain and trouble breathing. It was the chemo that made her sick.

What most people don’t realize is that chemo isn’t some cure or cold medicine you swallow fast to get better. Chemotherapy is so toxic that if you were to pour it on your skin you’d suffer rashes, burns, vomiting, dizziness, the list goes on. To Allison it felt like the worst flu. As if she was a juice box and some five-year-old with sticky hands had sucked all the fruit punch out of her. She was crabby. She couldn’t eat. When she wasn’t huddled over the toilet, she was curled in a ball watching “The Proposal.”

And in March 2023, Allison went into heart failure due to doxorubicin, a form of chemotherapy, also known as “the red devil”. Due to its toxicity, a cardio protective medication was given just before the treatment.

Soon after Allison experienced side effects. Her hands and feet turned purple, her resting heart rate was 130/140, her blood pressure was through the roof and she couldn’t walk 10 feet without getting out of breath. A walk down the hall was a marathon for Allison.

Within the first two months, you could see her ribs. Allison could feel the little independence she’d gained as a high school girl slipping through her finger tips.

“The second night I had to deal with my first shower,” Allison said. “I had a pick in my arm, it was sore so I couldn’t bathe myself and I had to learn to be vulnerable with my mom. She saw me naked. She hadn’t seen me like that since I was born. You have to be comfortable with it because it’s either your mom or a nurse. So obviously I’m gonna pick my mom. I had to hit the call button to go to the bathroom. I had people making sure that I took my medicine and if I was eating. I felt like a baby.”

Andrea graduated from JCCC with her RN in 2010, she’d left her nursing job at the hospital job over four years ago. Now she works in hospice. She’d grown accustomed to the suffering, to the anxious tapping of fathers and silent tears of mothers, each asking the same questions. She found a purpose in granting patients comfort in their final moments.

But no amount of schooling, testing or case studies would prepare her for what was to come.

“I felt a lot of guilt because Courtney had all sorts of symptoms for a while and we explained them all away,” Andrea said. “That day in the doctor’s office I knew what we were looking at. Twenty five pounds of weight loss, she had no energy, she felt full even when she didn’t eat, she had swollen lymph glands all over her throat. Before it was tummy trouble and anxiety. I felt like I failed as a nurse mom for not coming to her sooner. She was at stage four cancer when we found her.”

Andrea dropped everything. She was there to watch “The Princess and the Pauper” and read Allison the Amelia Bedelia books.

She left her job, her own mother practically moved in the day she got the call. She witnessed Allison’s room convert to a junkyard and sat with the fear of her daughter losing the spark she once carried.

Never before had she missed a game of Tyler’s or one of the million sports Piper played, now she missed many.

“One of my good friends from high school, her daughter, had the same cancer two years prior in 2020,” Andrea said. “She recovered. Ainsley had it her senior year as well. It was nice to see someone make it to the other side. I knew that the cure rate after the first six months of treatment was 90 percent.”

It gave her hope.

Meanwhile, Allison began to live through her siblings, wishing the annoyance of every other person she stumbled across say “I’ll pray for you.” or “everything’s gonna be alright.” would fizz out.

She’d listen to her brother and his girlfriend giggle in the kitchen as they made funnel cakes or listen intently to Piper’s 6th grade drama. She craved normalcy.

She tried going back to school, which didn’t work out initially and started making her bed, and floor somewhat visible.

Allison became closest with her Aunt who recovered from breast cancer and often said things like “You are brave.” or “You can do this,” instead of “It’s gonna get better,” because she realized it was a choice.

Each day Allison attempted to pull herself out of the steep hole that was her depression. Whether this was by going to physical therapy every weekday from March to June, spending more time with Jake, “I’m not afraid to admit that he’s my favorite sibling,” or forgiving her father.

May 10, 2023, the doctors informed Courtney Allison that she’s in remission.

She still worries for inevitable fever to spike.

She still worries for her mom and her younger siblings.

She still worries that it will come back.

“I always had to remind myself that it’s something that happens, not something that somebody did to me,” Allison said.

Her last round of chemo was over five months ago.

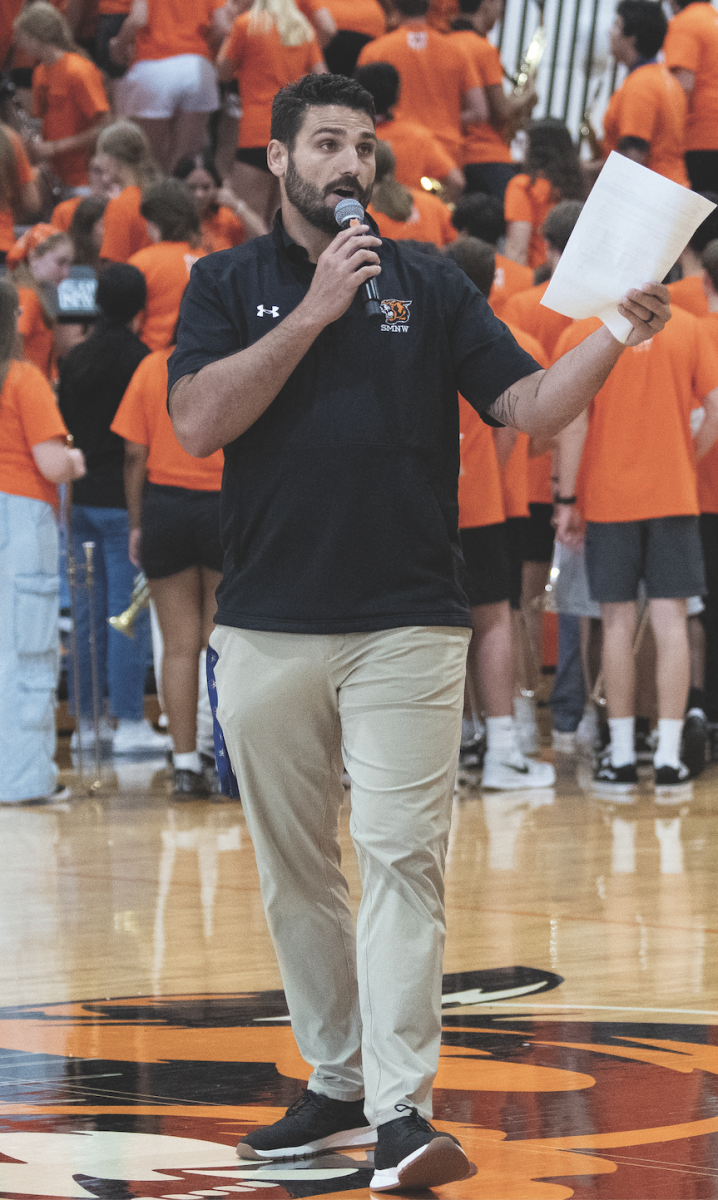

Now, Allison is a Spirit Club rep, assistant coaches cheer, picks up trash after football games and lab aids for Athletic Director Angelo Giacolone, one of her biggest supporters.

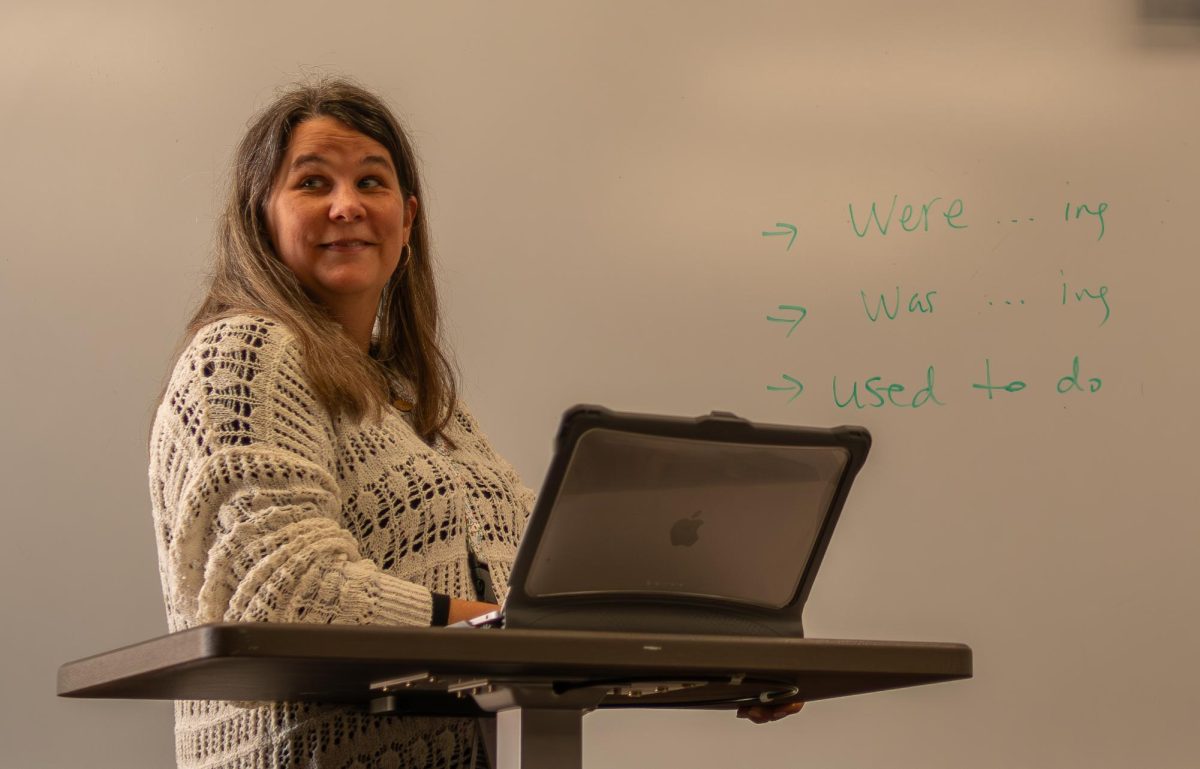

Allison has hopes of becoming a teacher, because maybe then one less kid will cry over fractions, maybe then one less kid will drop out, maybe then one less kid will feel alone in their struggles.

“I don’t wish it never happened,” Allison said, “I’ve gone through a rough experience I almost came out of it with more empathy than going in. At PT I saw kids who couldn’t walk there, kids in the waiting room that were way younger than me. A kid came in from the system with foster parents.”

May 10, 2023, Allison walks the halls of Children’s Mercy hospital, a row of nurses greet her with applause. She rings the cancer bell, reverberating against the linoleum flooring.

“I feel like I can breathe again.”

![Smiling, senior Courtney Allison watches her students Oct. 25 at Nieman Elementary. Allison has been coaching cheer for 2 years and teaches grades 6-8th. “[Moments I live for] are when I make a correction and I can see the students that are taking a correction and using it to get better and not immediately shutting down,” Allison said. “I feel like I'm more of a peer role model because I'm somebody closer to their age who maybe they could relate to a little more.”](https://smnw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Screenshot-2023-11-09-at-10.22.49-AM-1200x800.png)