July 26, 2023.

Senior Josie Malara was getting ready for a job interview when she got the text.

“Call me ASAP.”

Suddenly, she’s sprinting down the halls of Overland Park Regional Hospital, asking every nurse in sight if they knew where Will Ensley was.

Will Ensley, the boy she met her freshman year of high school. The boy who asked her to homecoming.

“I eventually found him.”

The boy she watched Little Miss Sunshine with and he complained the whole time.

“He was in the ICU.”

The boy she spent hours with at the park, swinging in hammocks as their parents left dozens of missed calls and messages.

“His mom hugged me.”

The boy she dragged to Spirit Halloween for fun, only to end up in his pickup once again, watching the sun set.

“She asked if I wanted to see him.”

The boy she Facetimed on Christmas, watching the eagerness he had putting Lego sets together.

“It didn’t look like him.”

The boy she spent a six month anniversary with, watching Nightmare Before Christmas in PJ’s when she said “I love you,” for the first time, and he said it back immediately with a smile on his face.

“I was in the room till they forced us all out.”

***

On July 26, Ensley, an incoming senior, was rushed to the hospital after injuries sustained in a nine car pile up. He passed away that morning.

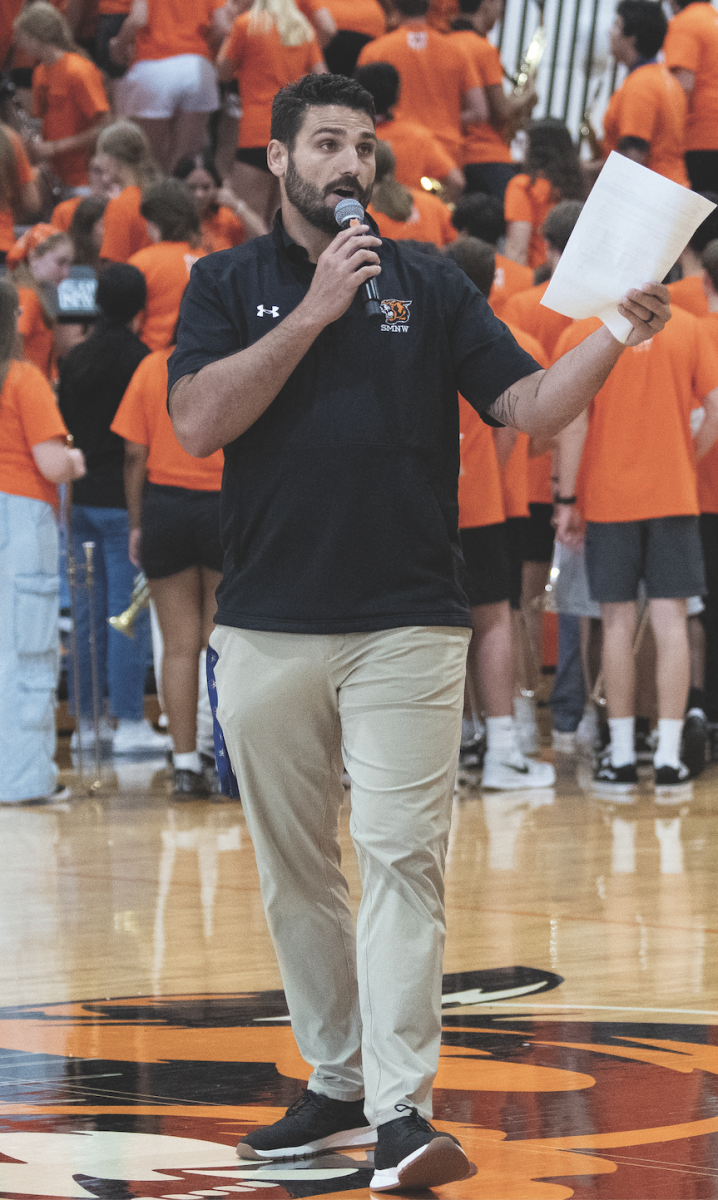

In a letter to Shawnee Mission Northwest families, Principal Lisa Gruman wrote, “Death is always difficult to handle, but especially when someone is so young. It will be important to recognize that all of us will need time to process what has happened and express our feelings.”

This story is about grief, the impact Ensley had on loved ones and the impression he left on everyone.

Like Ryan Lee.

He would never be the same.

Lee swam in high school and at the University of Kansas. He calls himself “a swim nerd.”

He never wanted to teach, not at first.

But 17 years in, he met Ensley

“A coach’s dream,” Lee said.

The first time Lee laid eyes on Will, he was barely old enough to ride in the front seat. He was afraid to put his face in the water. Varsity swimmer, senior Will Ensley, school record holder of the 50 yard relay split, was afraid to put his face in the water.

“Wow, this kid is not good,” Lee thought at the time.

Even so, Lee had made a connection, a friendship with a boy he met during the night program at Turner High School.

“I always ask my athletes to sacrifice the normal teenage stuff,” Lee said. “With Will, I never had to worry.”

Ensley always had to eat chicken, rice and sweet potatoes the night before a meet, and spaghetti and vegetables the night before that. He went to bed at 9:30 p.m. and had the same breakfast each morning. His walls were smothered with team pictures and medals. Still, to this day, at the center of Will’s desk is a tidy stack of notebook paper with lists of stretches for every day of the week.

Ensley had good grades, college credit, neat handwriting and the kind of notes people paid for. He was a good student, a good athlete, a good person. He was a creature of habit. He was disciplined.

But deep down, this well-mannered young man, who was told he’d have a bright future one day, was still a vulnerable little boy, afraid of the water. The one who trusted his coach, and soaked up his every word like pool water.

As the years progressed Lee and Ensley spent more and more time together, discussing practice, records and what he could do to help the girls swim team. He split times of Olympian swimmers as Lee watched in amazement.

They grew together.

They understood each other.

Now, Ryan Lee can’t step onto a pool deck without choking up.

“I think of him every day.”

***

The trip through Swan Drive is hilly, full of bright houses with brick driveways, surrounded by a forest.

A peace lily stood by the front door. Photos sat on the mantle of the stone fireplaces. A knit blanket folded over a rocking chair.

“I’m not even sure where to start,” Sharon Ensley, Will’s mother, said.

The house was quiet. Tissue boxes appeared on both sides of the brown couch.

“It helps to speak about him,” Randall Ensley, Will’s dad, said. “It helps us process it better. I don’t think I could keep it in, anyway.”

In the weeks since Will’s death, they have gone on bike rides and walks. Mr. Ensley is back at work part time as a sales rep. Several weeks of dinners, plants, texts and letters had been sent to the Ensley home. Their older son, Jack, is off at college.

Things are moving so fast, yet nothing’s changed.

Will’s bedspread is untouched, the grandfather’s watch he’d wear to school dances remains on his nightstand. His backpack, his pens, his “Well Dressed Wednesday” magazine are just where he had left them.

But there was nothing on his bedroom floor to explain his dislike for movies, his trip to the Oregon Coast, or the time he caught a catfish in a kayak and it pulled him around the cove. There was nothing in his notebooks that described the way he’d lay on the dog when he was little or the time he made potato pancakes for a Friendsgiving.

His favorite TV shows, ‘Stranger Things’, ‘The Umbrella Academy’ or ‘Breaking Bad’ weren’t stitched in his letterman jacket. There was nothing to show for the time he went to Raising’ Caines, got food poisoning and was scared to go back.

“I’d like to get through a day without crying,” Mrs. Ensley said. “I know it will come but it’s so hard to live without him. I laugh sometimes thinking about his pronunciation of things when he was a kid or the way he danced.”

There will always be reminders.

There will always be days when Mr. and Mrs. Ensley feel like a dark cloud that no one wants to look up and see looming over them. They will always miss their son, and nothing can change that.

“Don’t take your friends and family for granted,” Mrs. Ensley said. “Love people while you have ‘em and we know that Will was loved. So that makes me feel better, but makes it ache more too, you know. Kids don’t always think that they need to tell their friends how much they love them but they really should. I know there are kids that didn’t get to say what they wanted to to Will until after he was gone, and plus —”

Mr. Ensley jumps in, “It isn’t just kids, it’s a lot of people.”

“Yes,” Mrs. Ensley says, “but you don’t think you’re going to die.”

“Lots of people go through life thinking them and their friends and family are all kind of bulletproof and they’re not,” Mr. Ensley says.

There’s a long pause.

“Life is fragile.”

***

A few weeks ago Tad Lambert was planning a trip to Canada. Planning was an overstatement.

Most people take their senior trip to Mexico, New York, Miami or California.

But Lambert is choosing Canada.

It was stupid, but it wasn’t.

These days nothing was out of the question, whether it meant roaming around Nebraska Furniture Mart on a Tuesday afternoon, taking on a few extra shifts at his summer job in Lakeview Village, scrolling through his camera roll or grabbing his keys for a spur-of-the-moment McDonald’s run.

It wasn’t because he wanted a new bed frame, needed the money or had an insatiable hunger for a quarter pounder with cheese.

He wanted to feel something. He needed a distraction

It had hardly been three weeks since he attended his best friend’s funeral. And already it felt like everybody moved on.

While others were making dinner plans, taking IRP notes and selfies, Lambert was in a constant battle with his thoughts.

He hated to be alone.

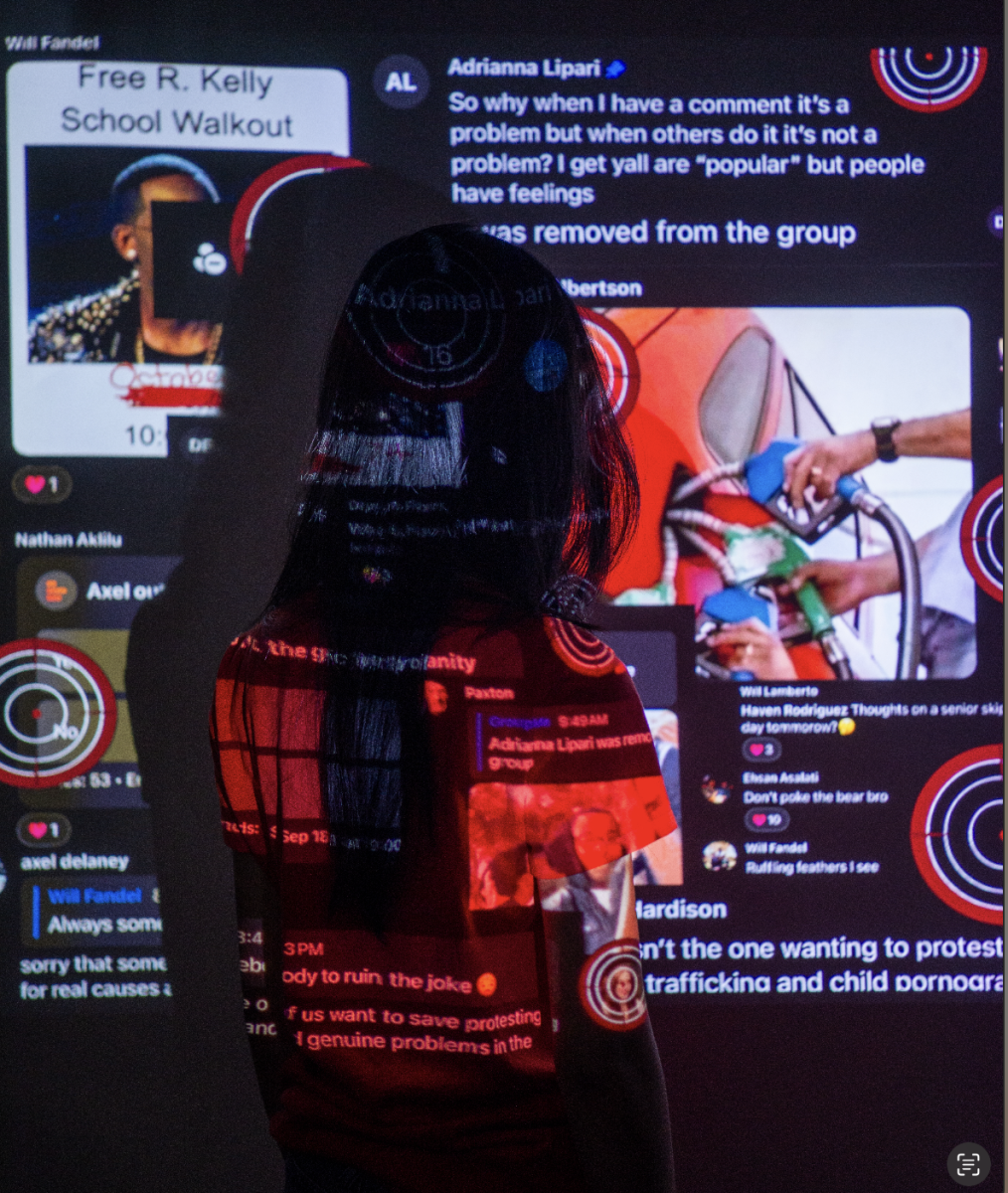

His Instagram story, meant to be his way of saying goodbye, a diary entry, a tribute to Will, already had double the likes as his second most liked post. Which were genuine and which weren’t Tad couldn’t tell, but either way it felt like a trend.

It made him angry.

It made him angry that they weren’t there in the hospital, that they hadn’t seen the excitement on Will’s face when he got a new water bottle, that they never showed up at his house unannounced for a “boys night,” that they never ate on his bedroom floor as Will did homework, or screwed around with Happy Meal toys.

Others got sad at the mention of Will in school assemblies, or emails to parents or the senior tribute on the football Instagram. For Lambert it’s every time he walks through the front doors, every time he sees a white truck on the highway, every time he opens messages.

It’s all the time. It is every day.

Because no 17-year-old should have to walk up to a casket, watch it lower to the ground, shovel a scoop of dirt.

No 17-year-old should have to lose their best friend

No 17-year old should have to graduate without them.

***

Mr. Ensley sets his son’s urn in the ground. He places a shovel of dirt atop it. One by one, members of the boy’s swim team walk up and pour a small vial of SMNW pool water into the ground with Will.

Josie went home and watched Little Miss Sunshine that night, her favorite movie, the first movie she ever watched with him. She still has his sweatshirt, the one she got him in Arizona, and sealed in a plastic bag, so it never loses his smell.

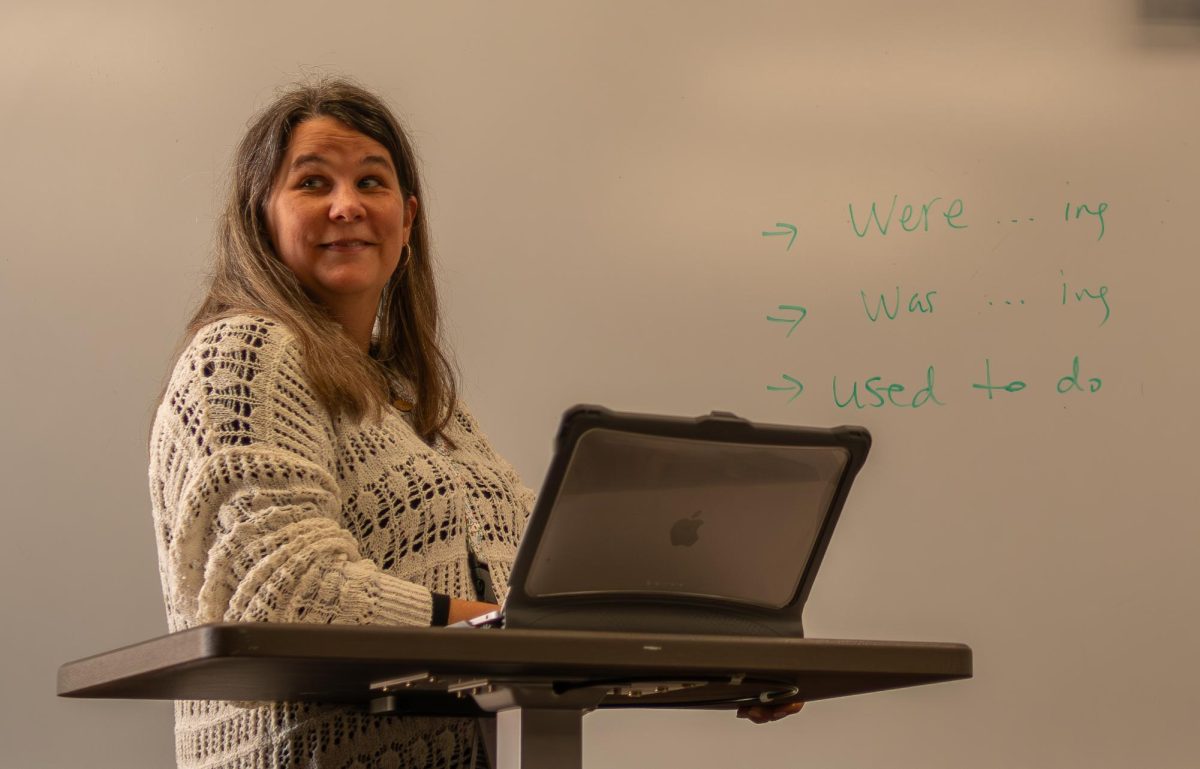

The first day of school, all eyes were on her. Once a week, she meets up to talk with the Ensley’s. She still has AP Psych, Environmental Ed and Independent Reading with Mrs. Anthony.

She went to Sonic after Bonfire and ate pancakes on paper plates at Senior Sunrise.

She’s not planning on going to homecoming.

“Can’t do that,” she says.

She’s still a teenager.

As for finding hope.

“I’m still figuring that out.”

But everyday, she tries.