COVID-19, One Year Later

One year after the discovery of COVID-19, the virus has changed every aspect of life

Commonwealth Media Services: Nat

“State Public Health Laboratory in Exton Tests for COVID-19” by governortomwolf

January 27, 2021

Just over a year after the first case of the virus was discovered in Wuhan, China, COVID-19 has forever changed life around the world. For many, the disease has taken everything—family, friends, money, jobs, life experiences and so much more. But with a speedily developed vaccine beginning the first stages of distribution worldwide, there seems to be an end in sight for the first time since December 2019.

The first known case of COVID-19 in the United States was diagnosed Jan. 21, 2020. That same day, Chinese health officials confirmed that the virus could be transmitted person-to-person, and that the disease had killed four and infected 200 in China. The escalation in cases and deaths in the days that followed prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a Global Health Emergency on Feb. 3. By March 11, COVID-19 had met all three of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s criteria to be classed as a pandemic: illness resulting in death, sustained person-to-person spread and worldwide spread. March 13 was the next turning point for COVID-19 in the United States — President Trump declared a national emergency, which allowed the government to unlock funds and enact policy to fight the spread of the disease. What happened next was something most Americans have never experienced in their lifetime. Work shifted to a remote setting, school was postponed and eventually cancelled, civilians were placed under lockdown and masks became a commonly used item during limited public outings

Healthcare

The sudden escalation of the COVID-19 pandemic stunned many, especially those working on the front lines in the medical field.

“In the first week of March, we had one patient come in with a cough who had suspected she had COVID,” Overland Park Regional Medical Center Nursing Supervisor Fred Opuni said. “We sent in one nurse in a full protective suit to treat her. She tested negative. We thought that was the furthest this would go.”

But that was nowhere near the furthest this pandemic would go. OP Regional has had to take drastic measures to reduce the spread of COVID within its facilities and limit strain on healthcare workers. They’ve temporarily closed their free-standing Emergency Room of Shawnee, in an effort to consolidate resources and employees at their main building. They’ve required that all their maternity navigation appointments, meetings with a labor and delivery nurse to plan for the birth, take place over the phone. They’ve also had to limit patients to only one visitor per stay, meaning each patient gets only one designated visitor each day and they are not allowed to change their designated visitor from day-to-day. Additionally, visitors must check in at one of three screening points and are not allowed to check in after 9 p.m.

“The visitor rule has been one of the toughest parts of it all,” Opuni said. “Kids have to come in for procedures with only one parent. Moms are having babies with only one person in the room.”

Despite the drastic changes in procedure, OP Regional and other local hospitals remain bustling centers of activity and continue to play a vital role in helping the community through this pandemic. OP Regional is accepting community donations of N-95 and manufacturer-grade surgical masks (they cannot accept homemade masks), disposable gloves, goggles and eye shields, industrial soap and antibacterial wipes. They encourage those who wish to make financial donations to send them to the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) Healthcare Hope Fund, which provides aid to healthcare workers and their families.

Vaccine

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized two vaccines for emergency use to prevent the spread COVID-19. The Pfizer vaccine is approved for use in individuals age 16 and older, and the Moderna vaccine is approved for ages 18 and older. Both vaccines are administered by injection into the muscle, typically in the upper arm. Both are given in two doses; the Pfizer doses are given three weeks apart, while the Moderna doses are given one month apart. Both vaccines may result in side effects including fatigue, headache, fever, nausea and injection site pain. Recipients will likely be asked to stay at their place of vaccination for a period of time after receiving the vaccine for monitoring in case of an allergic reaction.

Vaccine rollout procedures vary by state, with some states moving faster than others. As of Jan. 22 at noon, Kansas has administered 143,856 vaccines, including first and second doses. Kansas has divided the rollout into five phases, prioritizing essential workers and elderly residents. Phase one includes health workers, long-term care facility residents and pandemic response workers. Phase two covers people age 65 and older, high-contact critical workers and people who work or live in congregate settings (facilities licensed by the government, such as homeless shelters and correctional facilities). Phase three includes people aged 16-64 with severe medical risks as well as other critical workers. Phase four covers people aged 16-64 with other medical risks. Phase five will vaccinate the rest of the Kansas population aged 16 and older, as well as children, if research of vaccine effectiveness indicates that children may receive the vaccine at that time. Kansas is currently in phase two of the rollout plan.

The vaccine costs are also completely covered by all of the major insurance companies. For those without insurance, the government is working on programs to minimize or eliminate all out of pocket costs. The plan for mass vaccine distribution will ideally be the same for any other vaccine—walk in, fill out information, get your shot and go on your way.

“I think there will be a rush, just like when an iPhone comes out,” Rempel said. “The first four days its a rush, day five and six it’s busy, day seven and on you can just walk in.”

Some of the biggest questions facing the distribution teams are: when exactly will the vaccine be distributed to the mass public and more importantly, when can people get back to “normal” life. The answer however, isn’t that simple.

“ probably won’t happen in really big numbers until early spring,” Walgreens senior vice president of technology Steve Rempel said. “I think it’s probably not going to be until summer we get down to the healthiest.”

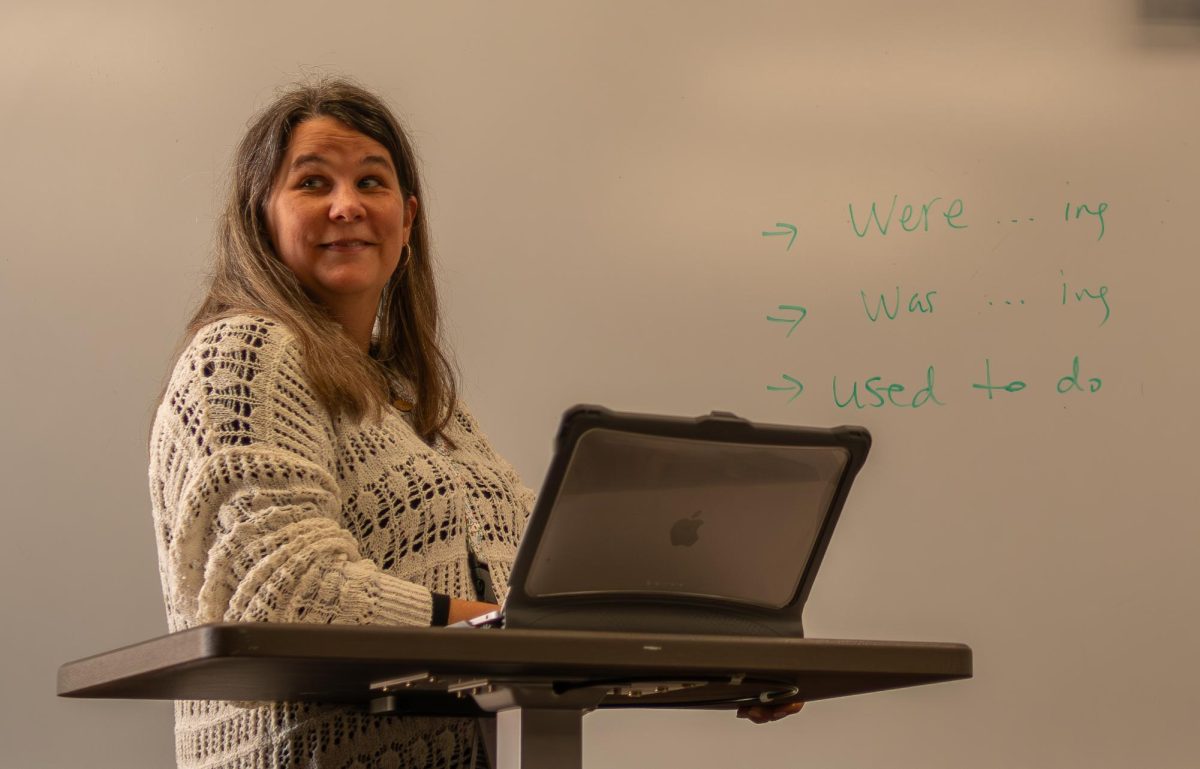

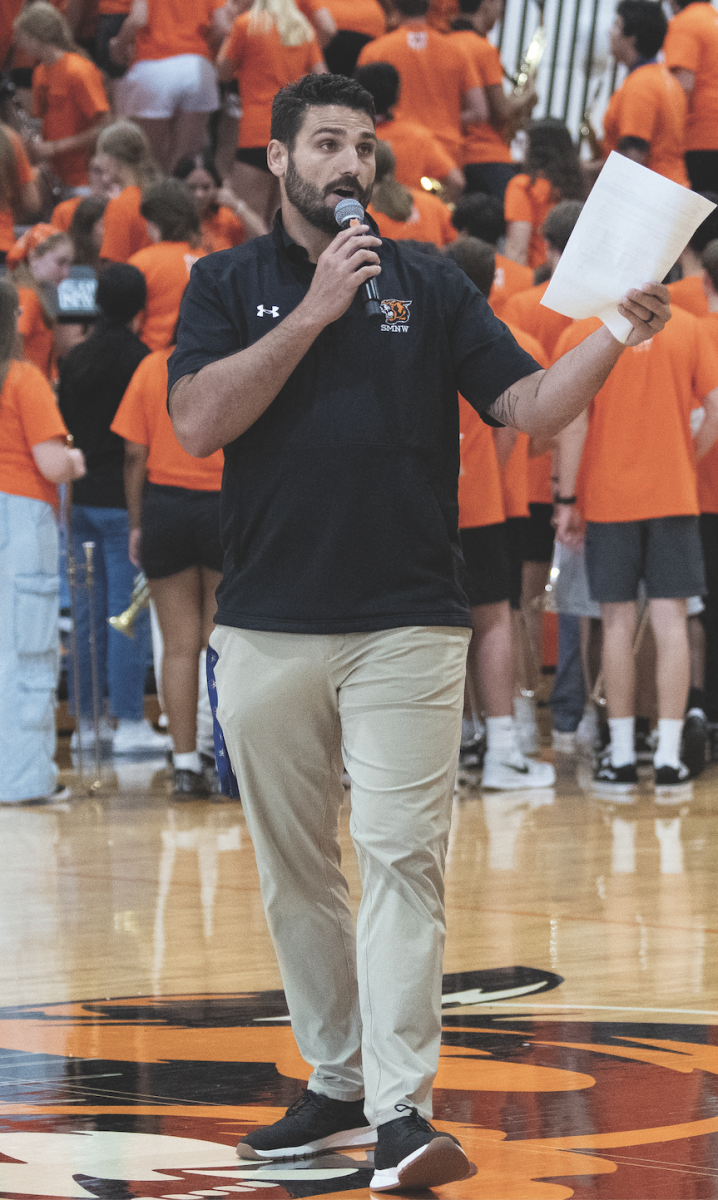

Education

For the Northwest community, the way COVID-19 has changed education has been a primary influence in our lives. The jarring shifts between remote and hybrid learning throughout the school year have severely damaged student morale.

“Hybrid is the worst of both worlds,” sophomore Savannah Miner said in a poll conducted by the Passage. “You only get to see your teachers a limited number of times a week and the switching from home to in person halfway through the week is tiring. At least in remote you can be settled in at home.”

Though the changes in teaching style this year have taken a toll on most Northwest students, some are willing to endure it to ensure the safety of others in the community.

“I obviously prefer hybrid, as I’d like to finish my senior year as normally as possible,” senior Trevor Hale said. “But if the situation doesn’t improve, I’m glad to sacrifice a small fraction of normalcy to help in possibly saving lives.”

The first variant, B.1.1.7, was discovered in the United Kingdom in September. It quickly became common in southeast England and has since spread to other countries, including the United States which has had 195 total cases. According to the CDC, it spreads more quickly and easily than other variants, but has not yet been proven to cause more severe illness or increase the risk of death.

Another variant called 1.351 was discovered in South Africa in October. It developed independently of the variant in the United Kingdom, but shares some mutations. It has spread outside of South Africa, but has not yet been found in the United States.The third variant, P.1, was first found in four Brazilian travelers at an airport in Japan. This variant contains mutations that might affect its ability to be recognized by antibodies, but has not been proven to increase the disease’s severity. This variant has not reached the United States.

CDC officials are currently investigating whether these variants will respond to current treatments and vaccines.

“We luckily haven’t had any cases come into our hospital with one of the new variants,” Opuni said. “But I will say that if are more contagious, that will only put a bigger strain on our staff and facility, and facilities across the country, when these cases start appearing in our hospitals.”

New Variants

Though the introduction of the vaccine has many hoping for an end to the pandemic, the discovery of new COVID-19 variants may dash those hopes.